The Parramatta Sack Murder: A 1937 Sydney Mystery of Love, Jealousy, and Unresolved Shadows

The Gruesome Discovery

In the fading light of a late spring afternoon in 1937, the tranquil Lake Parramatta Reserve in Sydney’s western suburbs became the unlikely stage for a gruesome discovery. On November 30, orchardist Francis John Gilbert was inspecting the boundary fence of his brother Thomas’s peach orchard when he noticed something amiss: a chaff bag slumped amid a clump of wild quince bushes, partially concealed against the low paling fence. Expecting perhaps discarded farm waste, Gilbert approached the bag. What he uncovered instead was a horror that would unravel into one of the era’s most talked-about crimes—the “Body in the Bag” case, or the Parramatta Sack Murder.

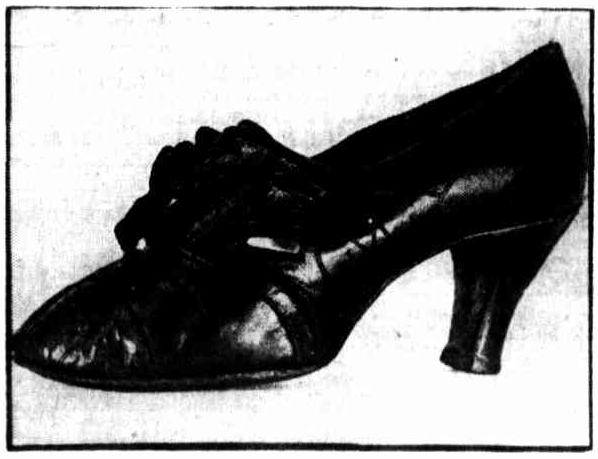

The body was that of a young woman, her legs drawn up in a fetal position, suggesting she’d been placed in the bag soon after death while rigor mortis set in. One chaff bag had been pulled over her head and shoulders, leaving her torso partially exposed, while another was thrown loosely over her legs. The corpse had lain there for 10 to 14 days, exposed to rain and sun, rendering her face unrecognisable due to advanced decomposition. She was well-nourished, estimated to be 25 to 35 years old, 5 feet 3 inches tall, and weighing approximately nine stone. Her attire spoke of a woman of style. She was found in a striped fuji silk dress with short sleeves, two black buttons above the waist, and a bright red ribbon sash; pink corsellettes branded La Mode Foundation Garment; a light blue milanese slip; a pink brassiere; brown stockings; one black lace-up shoe (size 3) with blade lace; a blue fabric rubber-lined raincoat with large white spots; and a half-inch mottled light green composition bangle. Her fingernails were red-tinted, her brown hair fairly long, and dental details included a full lower jaw set, two missing bicuspids and a molar in the upper jaw, with one gold filling.

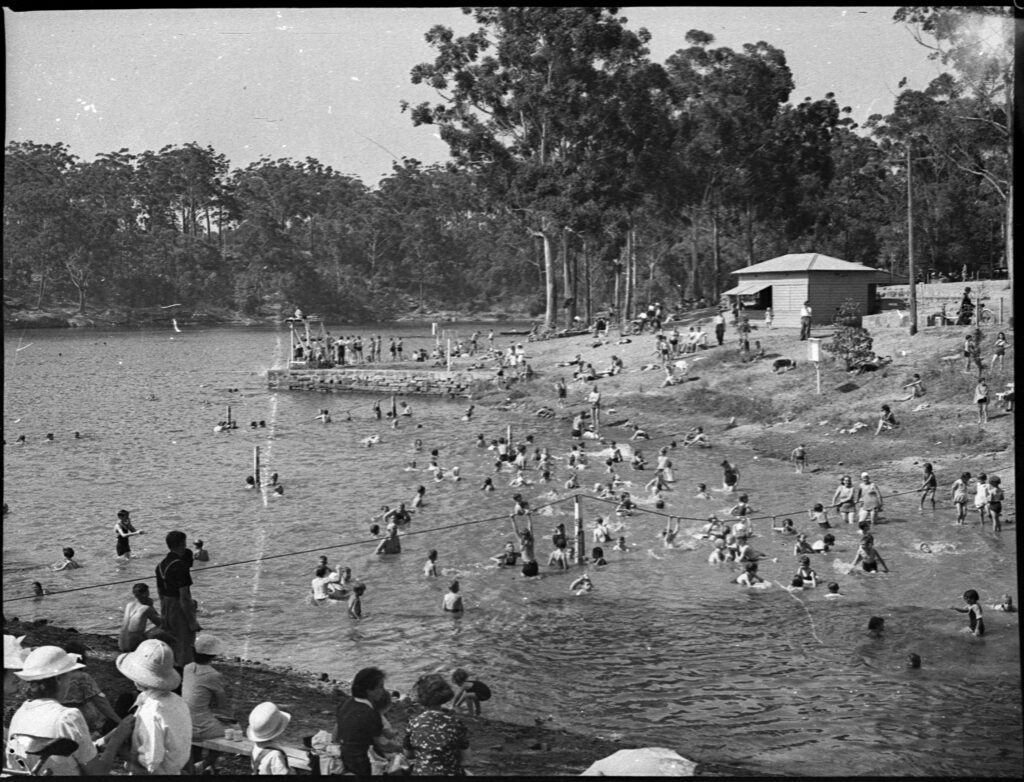

The location itself added to the enigma. The reserve was a popular spot known locally as “Little Coogee.” Hundreds of cars traversed the circular drive weekly, a bus service ran regularly, and at night, it was known as “Lovers’ Alley,” dotted with parked couples. The body lay just 30 yards from the exit, near a road used by bathers and picnickers, yet it went unnoticed. Two fence palings were broken, likely from heaving the body over the 4-foot barrier. Detectives, including Sergeant Allmond, Bowie, and Thompson, swarmed the scene. Early theories dismissed a local killer: no Parramatta resident would choose such an exposed spot when denser scrub or the lake’s backwaters offered better concealment. The perpetrators—likely more than one, given the body’s weight—were strangers, perhaps aiming to dump her in Lake Parramatta but deterred by nighttime swimmers. The bags, unmarked and utilitarian, suggested she’d died in a house, shrouded for transport in a car that never left the road, as no tyre marks were found on the grass.

The Initial Investigation and Identification

Sydney’s press erupted with headlines like “Woman’s Body Found in Sack ” and “Parramatta Murder” detailing the macabre find. A post-mortem by Dr. A. A. Palmer ruled out bullets, knives, or broken bones but couldn’t pinpoint the cause—decomposition had erased surface evidence. Poisoning was floated, with samples sent to the Government Analyst. Battering remained possible if marks had faded, but suffocation or strangulation loomed as alternatives. Jealousy emerged as a motive based on the victim’s vibrant appearance, suggesting her life was cut short by passion’s dark turn.

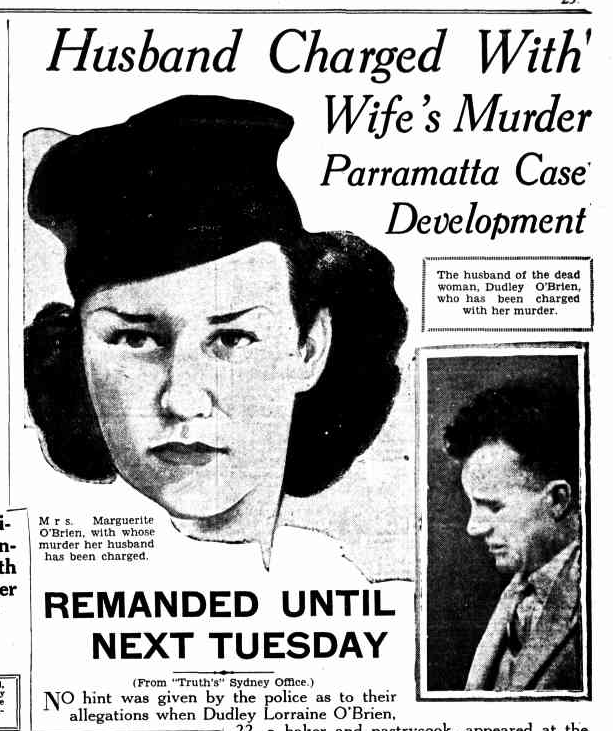

Identification came swiftly. On December 1, a friend read the clothing description—particularly the distinctive blue raincoat with white spots—and contacted the C.I.B. Viewing the items at Central Police Station, she confirmed they belonged to her missing acquaintance, last seen on November 22 heading to work. The victim was Margrethe Greta Boesen, 20, from Caulfield, Victoria, using her maiden name in Sydney. But she was married and legally known as Mrs. O’Brien, wed to Dudley Lorraine O’Brien since 1935. Born in Darwin, Greta had lived in Windsor, where her father managed a butter factory. She married Dudley while in her teens—a boy-girl romance—but after their son Neville’s birth in 1936, strains mounted. Dudley struggled for steady work, and Greta sought independence, placing Neville in care and working as a typist in city offices, often concealing her marriage to secure jobs.

Greta’s life in Sydney was a blend of secrecy and vivacity. She shared a Bayswater Road flat with Enid Carr, who knew her as the single “Miss Boesen.” Greta was “sturdy, vital, fresh-faced,” with “fine features and attractive eyes,” dressing tastefully to charm. Admirers abounded: phone numbers jotted in her flat led to men who’d gifted flowers, called frequently. Jack Paxton, a motor driver, admitted intimacy before learning she was married—they’d dined, danced, even sat in the Botanic Gardens. “Lou” visited for cards. Even her boss, James Wilson, 45, penned letters with terms like “Dearest” and “My eyes are entitled to a feast,” though he denied romance, calling them “just notes.” A mysterious black box she guarded, containing £300-£400 “for a friend,” vanished, fueling speculation of shady dealings from her firm’s repossession work tracking absconders and demanding payments.

The Grieving Husband

Meanwhile, at Greta’s funeral, her husband, Dudley, wept uncontrollably, calling her name, supported by relatives. “How could anyone do this?” he sobbed to reporters. His mother-in-law, Mrs. Boesen, embraced him. Dudley cooperated fully with the investigation, detailing their stormy marriage but insisting on love. Police noted his alibi that he had been out dancing the night she went missing and pursued other leads. Headlines screamed of a “mysterious killer,” perhaps a jealous stranger hauling her body in a car, chaff bags from a rural source.

Detectives Close In

Police theories coalesced. It was revealed that Greta vanished on November 23 after work. The missing items at the crime scene—the right shoe, halo hat, gloves, handbag—suggested there may have been a struggle. Her body would have been heavy and rigid, and thus requiring accomplices for disposal. The chaff bags implied a rural tie, perhaps a country admirer who stayed in a Kings Cross hotel, as many country folk were in the habit of doing at the time. However, the theory of jealousy dominated: “Miss Boesen” enjoyed life’s freedoms, and this may have invited envy.

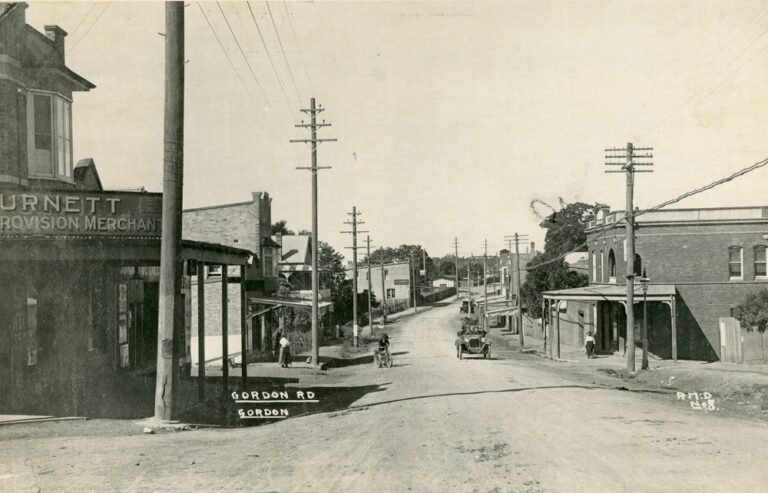

The Daily Telegraph, 3 December 1937, P.1

Optimism grew with the revelation of clues like a lifting jack near the body, tyre marks, and burnt rubbish hinted at a breakthrough. Public tips flooded in with claims the missing shoe had been found, but none matched. Detectives reconstructed the events leading to Greta’s final breath while Dudley’s grief painted him innocent, and friends vouched for his gentle nature and post-illness fragility. As weeks passed, the press reported that detectives were honing in on a suspect, and although the case seemed poised for a dramatic capture, the public was deprived of any hint as to who it could be.

On December 5, police made an unexpected announcement. They had caught their suspect, and he was in custody. He had confessed, after initial denial, meeting Greta, driving to Liverpool and arguing over her admirers. “She teased me about Jack [Paxton] and other lovers… she went limp in my arms, my hands on her throat.” Panicked, he said he had circled roads, then frantically dumped her by the Parramatta Lake. “I loved her… I didn’t mean her harm.”

“She was my wife!”

Evidence of Uxoricide

Dudley O’Brien had drawn early suspicion, though detectives allowed him to play the role of grieving widower while they built their case. Born into a prominent Melbourne family, his grandfather William Henry O’Brien had left the family a fortune, and yet Dudley baked pastries amid financial woes. Their marriage was initially described as happy, although it became fractured due to repeated separations. Dudley had visited her Kings Cross flat, and he knew her haunts. On November 20, he had seen her with Paxton at King’s Cross, introduced casually but perhaps igniting rage. Evidence had started to mount as witnesses placed him near her office on November 23, waiting for a “girlfriend.” A lifting jack had been found near the body that matched the make of his vehicle. Tyre tracks at the scene of the crime were also a match. A man who purchased the same make of chaff bags in Leichhardt fit his description. The missing handbag had surfaced in a blackberry bush near his cousin Ronald Carey’s store, where Dudley stayed post-illness, and incinerated rubbish hinted at destroyed evidence.

The Inquest

The inquest into the death of Margrethe O’Brien opened on December 16, 1937, at Newtown Court before Parramatta District Coroner Mr. G. R. Williams, with Dudley Lorraine O’Brien present in custody. Witnesses provided key testimony on the first day. Enid Estelle Helen Carr, a window-dresser from Darlinghurst’s Kellett Street who had shared the Bayswater Road flat with Greta for six weeks, identified the clothing as her friend’s, including the blue-spotted raincoat. She last saw Greta alive on November 23 and noted a photograph of Dudley in her room, whom Greta described as someone she was “keeping company with.” Carr admitted Greta had many male acquaintances, including Jack Paxton (with whom she had a 7 p.m. appointment that night) and “Lou,” but insisted Greta never mentioned being married. Dr. A. A. Palmer, Government Medical Officer, described examining the body at the scene—one bag over the head, another over the legs—and finding no gross injury, fractures, or poison (per analyst). He concluded death could have been caused by choking via finger pressure on the throat, but decomposition prevented certainty; very slight pressure might cause instantaneous death from shock.

The inquest continued the next day at Glebe Court, focusing on Dudley’s movements and confession. Ronald Carey, Dumbleton storekeeper and Dudley’s second cousin, testified that Dudley stayed with him from November 22 after hospital discharge. On November 23, Dudley left around 4:30 p.m. to visit his son in Ashfield, phoned at 5 p.m. saying he was going to a Ginger Jar cabaret dance, returned late, and the next day burned rubbish in the incinerator. Herbert William Dauth and James Wilson from Harrington, Wilson Pty. Ltd. (Elizabeth Street) detailed Greta’s employment as a stenographer under “Boesen”; Wilson denied an affair despite cross-examination on endearing letters (“Dearest,” “Darling”). Mervyn Boughton saw Dudley in Elizabeth Street at 5:10 p.m., November 23, waiting for a girl. John Alfred Coombe sold two chaff bags to a man resembling Dudley. Sergeant Ducie found the handbag in Dumbleton’s blackberries.

Detective-Sergeant Allmond presented Dudley’s statements: the December 1 denial (Ginger Jar alibi, no knowledge of harm) and December 5 confession (argument over Paxton/other men, hands on throat, panic disposal at Parramatta, burning items). John Paxton admitted knowing Greta 16-17 months, past intimacy before learning of marriage, meeting Dudley on November 20 (casual introduction). Detectives Thompson and Wilks described Dudley, pointing out sites (bag purchase, disposal spot). Coroner Williams found Margrethe feloniously murdered by choking with Dudley’s hands at Liverpool on November 23, committing him for trial at the Central Criminal Court in March 1938. Bail not applied. Dudley reserved evidence on counsel’s advice. The inquest highlighted jealousy as the motive, with Greta’s hidden marriage and admirers central, but left the cause of death ambiguous due to the decomposition of Greta’s remains.

The Trial

The trial of Dudley Lorraine O’Brien opened in March 1938 at the Central Criminal Court in Sydney, drawing crowds eager for details of the Parramatta sack murder. Crown Prosecutor Mr. McKean, K.C., argued premeditation, pointing to the chaff bags purchased in Ashfield on November 23 as evidence of planning, combined with Dudley’s jealousy after seeing his wife with John Paxton on November 20 at King’s Cross. Witnesses revisited the inquest testimony. Detectives Allmond, Thompson, and Gordon confirmed Dudley’s character as decent and non-violent but outlined the circumstantial evidence: his car was observed driving through a local farm’s gates on the evening Greta was believed to have been killed, the matching lifting jack, handbag in Dumbleton blackberries, and incinerated items.

Dudley, slender with dark curly hair, gave an unsworn statement from the dock, emotional and tearful. He denied guilt, recounting their courtship, young marriage in 1935 at Kogarah, son Neville’s birth, separations, and financial strains that drove Greta to city work under her maiden name. On November 23, he met her in Elizabeth Street after shopping, invited her to ice skating (she declined for a drive), and they headed along Liverpool Road. Parking three miles past Liverpool, they lay in the car discussing reconciliation when an argument erupted over her handbag discoveries and confessions of intimacy with Paxton and Wilson. She reportedly said, “I love Paxton. He is a better man than you’ll ever be.” Dudley claimed he “clean lost control,” swung his arm saying, “Don’t talk like that,” and she went limp. He shook her desperately but failed to rouse her, emphasising, “I loved my wife with all my heart and did not want to harm her in any way at all.”

After the closing addresses—McKean stressing premeditated risk-taking, Dovey urging an accident in passion—Mr. Justice Maxwell summed up the trial, inviting a focus on manslaughter if murder was found unproven by the jury. The jury retired at 3:13 p.m. and returned at 5:50 p.m. with verdicts of not guilty on murder and, when asked, provided a not guilty verdict on the charge of manslaughter.

Dudley was discharged.

Lingering Doubts After the Trial

The acquittal of Dudley Lorraine O’Brien in March 1938 brought the Parramatta sack murder case to a formal close; however, it left a trail of unresolved questions and emotional fallout that echoed in Sydney’s press and among the victim’s family. The jury’s swift 90-minute deliberation—resulting in not guilty verdicts on both murder and manslaughter—prompted speculation about whether sympathy for the young, tearful husband had overshadowed the circumstantial evidence. O’Brien’s emotional unsworn statement from the dock, where he professed undying love and described the death as an accidental loss of control during a jealous argument, appeared to sway the panel. Post-verdict, O’Brien told reporters it had been an “ordeal” but expressed faith in the jury and justice system, adding poignantly, “I regret Greta’s death more than anybody else could do. You see, I loved her.” The press reported the outcome factually, with headlines focusing on the discharge, but the speed of the decision and reliance on O’Brien’s narrative—without direct corroboration of the fatal moment—fueled quiet doubts about whether intent had been too readily dismissed.

Greta’s family, particularly her sister Thora Boesen, voiced profound distress over the trial’s portrayal of the victim. In a statement to the press following the acquittal, Thora lamented the intense publicity, saying, “The whole thing has been terrible, and it has brought most undesirable publicity to our family. Horrible things have been said of my sister, who is dead.” She emphasised the family’s private grief and trust in Greta, implying the proceedings had unfairly cast her as provocative through revelations of her admirers and hidden marriage. Mrs. Boesen, Greta’s mother, had earlier shown support for Dudley at the funeral, but the trial’s focus on Greta’s relationships—Paxton’s admitted intimacy, Wilson’s affectionate letters—left the family feeling her memory had been tarnished to bolster the defence’s jealousy narrative.

Overall, while the verdict was accepted legally, the case’s ambiguities—decomposition obscuring the exact cause of death, O’Brien’s initial denial contrasting his confession, and evidence like the premeditated-seeming chaff bags—ensured doubts persisted in public discourse. The press, having sensationalised the “body in bag” mystery, shifted focus post-acquittal, but the swift outcome and emotional testimonies left many in Sydney questioning if justice had fully accounted for a vibrant young woman’s abrupt end amid secrets and passion. The Parramatta Lake Reserve discovery remained a haunting footnote in local history, a reminder of how love’s fractures could lead to irreversible tragedy.