The Mysterious Life of Charles le Gallien and his Violent Murder in Crows Nest.

A Horrific Crime Scene

At 11 p.m. Thursday 30th, September 1948, the body of Charles Louis le Gallien was found lying on the office floor of his engineering workshop at Crows Nest. Police described him as the victim of the most savage attack. His left ear was chopped off, he had a large stab wound at the back of the neck, and a large wound on his left side. Blood was splashed on the walls and desk.

A Miss Edith Grace de Groen made a frantic call to North Sydney Police earlier at 9 p.m., “Send Police to le Gallien’s shop at 319 Pacific Highway. I was expecting him to have tea with me tonight. He telephoned me about 7 o’clock and said he would ring me later. He rang me five times after that, and the last time, he said, ‘If I don’t ring in 10 minutes, you ring me.’ When I rang back, the phone was dead, and I could not raise him.”

Following the grizzly discovery, detectives arrived at the building and entered through the front door that faces the Pacific Highway. Superintendents James and Gorman and Detective-Inspector Ramus from the C.I.B., Detective-Sergeant J. Rodgers, officer in charge of the Scientific Bureau, Detective-Sergeant Hargrave, Detective Whiteman, and a large force of uniformed police went to the scene. A crime scene was set up under powerful arc lights where police took photos of the interior of the building and the body of the deceased.

The Scientific Bureau scoured the premises and its surrounds for evidence. They found blood in the washbasin, leading detectives to believe the killer had washed his hands before leaving the crime scene. However, there was no sign of a life-or-death struggle, as far as they could tell. It appeared the man had been attacked violently from behind as he stood over the phone on his desk and was left to slump down and die. Furthermore, Mr. le Gallien’s jacket and wallet were both missing. They postulated that perhaps the jacket was taken to cover the blood stains on the attacker’s clothing. It was declared a key piece of evidence to solve this crime. A search commenced.

The Investigation

On Friday, October 1st, detectives visited the Le Gallien family home at 75 Chelmsford Avenue, East Lindfield, to inform Charles’ family of their loss and to begin collecting any information that could help determine the deceased’s movements in the months and weeks leading to his murder. It was revealed that Charles was legally married and had four children. However, he had left his family twelve months prior and had been living at the exclusive waterfront Norwood Private Hotel at 61 Kirribilli Avenue, Kirribilli.

Police interviewed the family. The eldest son, Ross, aged 22, stated on the day of his father’s murder, he had been at a friend’s home at Wahroonga all day on Thursday, duco-spraying parts of a Tigermoth aeroplane, which he had bought the previous year. He left his friend’s home at about 8.40 on Thursday night, then went straight home to bed. He saw his father on the previous Monday morning at his engineering works and talked ‘ to him on business matters from 11 a.m. until noon. He added: “Since my father left us about 12 months ago, I have been the only member of our family to keep in touch with him. “I tried to ring him on Thursday between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., but as he did not answer the phone, and I was in a hurry, I did not contact him that day.” Harvey, aged 19, had been looking for a job all Thursday and was at a friend’s place in Wahroonga from 5 p.m. to midnight. Charles Ivan, 17, spent most of the day in bed until he got up and read the paper at 6 p.m. He went out about 7 p.m. to make a phone call, returned 15 minutes later, read, and went to bed. Mrs. Heather le Gallien, the deceased wife, confirmed all her son’s stories to be true. Then told the police she had spent the entire day and evening at home washing and ironing and retired at 10.30 p.m. Unfortunately, they could not shed further light on Charles’ movements leading to Thursday. But they did provide detectives with an understanding of the lifestyle their father lived.

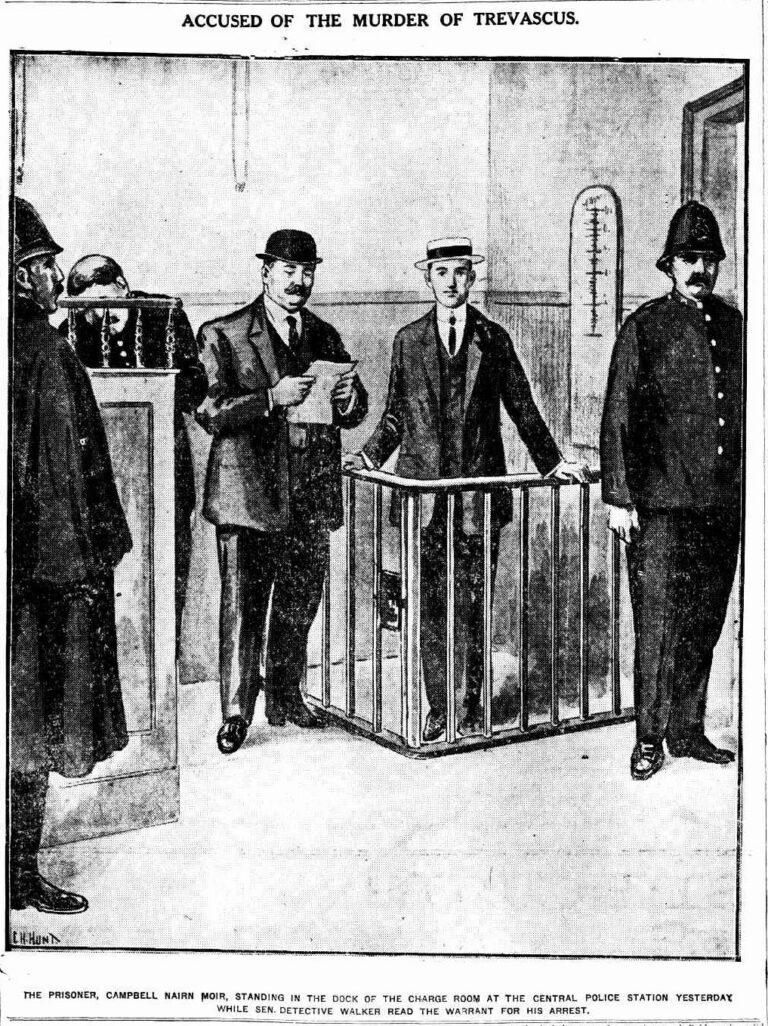

The photo above was taken the morning after the murder. 319 Pacific Highway was considered to be in Crows Nest in the 1940s. However, in present times it is considered to be in North Sydney. The photo below is 319 Pacific Highway in 2023. It appears the building has been altered to allow for off-road car parking in the front

Charles le Gallien was born in California, United States of America and migrated to Australia at a young age. He was a gifted engineer, and after marrying Heather Muir, was assisted by Heather’s family to set up an automotive mechanical engineering operation called Charles Le Gallien Mechanical Engineer, Gear Cutting& Turning Machine Works Company. The business became identified as a leader in the field and received several military contracts to supply the war effort during the Second World War. At 6ft 2in and 100kg in weight, Charles was a big man with a big appetite and lived a ‘high pressure’ lifestyle. He was known to consume a bottle of whiskey in his office daily, then consume half a dozen beers at the pub afterwards. Before leaving the family home in 1947, Heather le Gallien said her husband hadn’t come home sober in several years and was a violent drunk. He also had a big appetite for pursuing young, beautiful women. His family told detectives that he lived a double life. A family man and industrialist by day a playboy by night. He was rumoured to have had half a dozen lovers. Yet, only one the family knew for sure, Edith Grace de Groen, the woman behind the frantic call on the night of the murder.

The Other Woman

Blonde, beautiful and stylish. Edith Grace de Groen lived with her mother in a fashionable apartment at 97 Bent Street, Neutral Bay. The 30-year-old bookkeeper was a former employee of Charles le Gallien, having started her career at the company as a typist. She told detectives she had known Charles for about 12 years and she knew he was living apart from his wife. “He had meals at our home, but lived at Kirribilli. “I last saw him alive at 8 a.m. on September 30. “He had finished breakfast, and then left for his office.” Charles was supposed to have dinner at her apartment that evening at 7 p.m.”At 6.45 p.m. on the same day, he phoned me and we had a conversation.. “He phoned again at 7.20 p.m. and gave me certain instructions. “He instructed me to ring his office at intervals.” Edith rang at 7.30 then four more time before finally telling her if he did not call back in the next ten minutes, call the police. “I rang again at 9 p.m., but got the engaged signal. “I rang the telephone exchange, and ‘complaints’ told me the line was out of order. “I rang North Sydney police at 9.15 p.m., and visited the police station at 10.30 p.m.” She believed that someone was in the room with him, but she did not know who and didn’t believe he feared the person he was with. When asked what their relationship was, Edith denied that she and Charles were in an affair and insisted that they were simply friends.

Edith Grace de Groen

97 Bent Street, Neutral Bay, the home of Edith Grace de Groen and where Charles Gallien had planned to have dinner the night he was murdered.

Postmortem

A postmortem was conducted on the body at the city morgue in The Rocks only hours after the body was discovered. Dr. Percy said that le Gallien’s body had wounds in and behind the right ear, on the front and back of the neck, on the left side of the chest, in the abdomen and right little finger. The chest wound, in Dr. Percy’s, opinion, caused death, as the front of the heart was penetrated.

A Mysterious Life

The following day, police received an anonymous call hinting that le Gallien had been killed by a jealous woman whose advances had been rejected by the victim. Detectives began to suspect that the killer was indeed a female. In fact, they believed Le Gallien was arguing with a woman in his office that night and did not wish to reveal this fact to Edith de Groen, explaining the cryptic nature of his calls. It also explained why he showed no signs of fear when dealing with a woman they believed he could easily have overpowered. Police determined that with a razor-sharp knife, it would have been possible for a woman, particularly one infuriated with jealousy, in a fit of uncontrollable passion to catch him unawares with the one fatal blow that penetrated his heart. Then, as he staggered around his office, dislodging a few documents from his desk, his assailant could have inflicted the five wounds before slumping to his death on the floor. The woman, now covered in blood, covered herself with the man’s jacket and left the scene of the crime with two hours to spare before police arrived. So, who was the woman?

Police went on the hunt for the mysterious and very elusive harem of le Gallien’s lovers. First, they raided his Kirribilli hotel room and collected hundreds of papers. They found nothing to help them in their investigation. They interviewed over two hundred people, and not a single person could name or describe one of the women. It became very clear that everyone knew Le Gallien had lovers, but he was extremely clever in hiding them. Even his closest friends, whom he had drank with each afternoon for almost 15 years, confessed he was very discrete and secretive about his ‘after dark’ friends and kept their conversations mainly focused on sport.

The old Norwood Private Hotel sat at 61 Kirribilli Ave, Kirribilli and was an exclusive hotel, where it is believed Le Gallien kept his love nest. The building no longer exists.

The last time Charles was seen alive was when he walked out of the Union Hotel, North Sydney, at 6 pm after drinking a schooner, five middies and buying two bottles of beer to take away. Witnesses say he was sober, although the postmortem revealed a blood alcohol level of 0.107. He is believed to have been murdered approximately three hours later.

On October 2nd, Charles Louis le Gallien was buried at the North Shore Cemetery. Edith de Groen attended under twenty-four-hour police protection as she was the primary witness in the investigation. Yet, still, there was no new evidence to reveal the identities of the mysterious women or who the killer may be.

An Unexpected Suspect

At 11:30 p.m. on Tuesday, October 5th, detectives and uniformed police surrounded Wynyard Square, encircling a young man waiting at a bus stop. Detective Inspector Ramus pulled up in an unmarked police vehicle and approached the young man,

“Charles Ivan le Gallien?”

“Yes.”

“We have information that you were seen on a bus between East Lindfield and North Sydney at about 5.20 p.m. on September 30, 1948, and again at 6 p.m. on the same day outside the Catholic Church, North Sydney.’ ‘Charles Ivan said, ‘That was not me. As I told you before, I was at home and went out only twice to try and ring my girlfriend.’

Ramus replied, ‘We have certain information from a young man named Mahony, who has stated that you approached him to place a cyanide tablet in your father’s beer while he was drinking at the Union Hotel, North Sydney.’ ‘That’s a lie,’ exclaimed le Gallien, ‘I wouldn’t do anything like that.’

‘We also have information from a young man named Carroll that he had been approached by you to murder your father. Le Gallien replied, ‘That’s a lie. Carroll and I are bad friends.’ Ramus continued, ‘We also have information from a man named Turk who states that you approached him and wanted him to run over your father in a motor car and make it look like an accident.’ ‘That’s a lie,’ Le Gallen repeated. Ramus continued: ‘Your father’s coat and a sweater have been found in the bush not far from your home.’ ‘He replied, ‘That sweater is not mine. I have one at home. It is in the top drawer of the loughboy.’

‘Charles Ivan le Gallien, we have reasonable cause to suspect that you were implicated in your father’s death, and we have no alternative but to charge you with the murder of your father.’ He asked to see his mother.

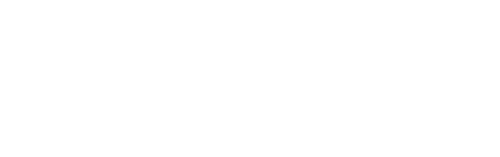

Charles Ivan le Gallien being escorted by detectives of the NSW Police.

Mrs Le Gallien came to the Central Police Station cells, and on hearing her son had been charged with murder, she sighed and said, ‘This is terrible. If my husband had not left home to live with Miss de Groen, it wouldn’t have happened’.’

The Inquest

The Coroner’s Inquest was held on October 20th. Hundreds arrived early to claim a seat in the public gallery and watch the boy accused of patricide in the sensational case that had played out in their morning newspapers like a serialised detective thriller. The members of the Le Gallien family entered the courthouse, accompanied by friends and supporters. Charles Ivan le Gallien, wearing handcuffs, was escorted into the courthouse by detectives. He was wearing a brown suit with a khaki shirt. His face was covered from the flash photography of court photographers with a handkerchief as he made his way through the crowd up the steps. Charles Ivan was represented by prominent defence barrister Mr James John Benedict Kinkead K.C.

Charles Ivan le Gallien being escorted into the Coroners Court at 104 George St, The Rocks.

Harvey le Gallien (brother) entering the Coroners Court

The witnesses and evidence were called into court, one by one. There was a stir in the public gallery when the elegant Edith Grace de Goren was called to the witness box. She told the court of the calls she made and received on the night of the murder.

Joseph Carroll, an apprentice plumber, said Charles le Gallien had told him that his father had sacked him. “He mentioned to me that he wouldn’t mind someone attacking his father,” Carroll added.

Sgt. Briese: What did he actually say? — I think he said something like “Do his father in.”

Carroll added “About June, 1947, he asked me if I’d join him in breaking into his father’s factory. He said there might be a lot of money there. He said the money was kept in a drawer of one of the benches. I told him at first I would not have anything to do with it. A month later we decided we would go out and break into the factory. We went out to his father’s factory about midnight one night.” Carroll said they climbed on the roof, removed a few tiles from the back of the building and climbed inside. Later the police came. In reply to Sgt. Briese, Car roll said le Gallien took no action. Carroll told Mr. Kinkead he had no grudge against young le Gallien. Mr Kinkead asked it is only a short time ago he gave you a hiding? — Yes. You wanted to stand over him for £3? — Yes. You and two friends went to a hall and asked him to come outside? — Yes. And instead of giving you the £3, he fought you? — Yes. I put it to you at no time did he mention of doing his father in? — He mentioned he would not mind seeing someone else do him in. Who was present? — I was the only one present. Have you ever been in trouble before? — That was the first time when we broke into Mr. le Gallien’s garage. Carroll said that 30/- was stolen. Mr. Kinkead, you took that? —Yes.

Constable Klyne said that le Gallien was fighting with Charles when he and Sgt. Duffy went to the home on November 8, 1947. “I saw young le Gallien hit his father in the face,” Klyne added. “Sgt. Duffy and I separated them. I took the youth to the back of the house. He was enraged.” He said, “I will stab the bastard. He is no father to me, the way he treats my mother. I will cut his heart out. The young le Gallien was wearing pyjama trousers which were torn and blood-stained. He was coatless. The father had been drinking and was knocked about a bit about the face. The father was fairly well under the influence. The father would take no action against the boy.” Constable Klyne said some of Charles Ivan’s friends were in the house. Mr. Kinkead: They were sober and respectable? — Yes. Constable Klyne said he did not know that the father had come in and called them scum and told them to get out of the house.

Reginald James Turk, employed at Beau Pen Co with Charles Ivan. “In April 1948, there was a discussion between Charles and myself about firearms,’ said Turk. “He also asked me if I could drive a car, and I said I couldn’t. He then said something about ‘killing his father.’ There was a general discussion about ways and means of killing his father, something about either running over him or shooting him. He asked me to kill his father for him by knocking him down with a car, but I refused,” said Turk. “About 12 weeks later, I met him again in Castlereagh St., City, and he said, ‘Will you kill my father now?’ He said it could be done, anyhow. He told me his father had a garage in North Sydney. He said he wanted the murder to look like an accident to collect the insurance. ‘The sum of £800 was mentioned to me. He said he would give me a written guarantee that I would get it. I told him I wouldn’t do it.“

Mr. Kinkead: What did you say to him to lead him to believe ‘you would commit murder? — What I said was that Charles discussed ways and means of killing his father. Do you say you would hire yourself to kill a man? — No. Was this a serious conversation? — You have heard boys of our age talking together. It was said in a joking fashion. Was it suggested the father was leading a double life? — Yes. Charles mentioned it. Was there any conversation about the father’s home life and about his drinking? — Yes. It was inferred he was a rotter. You said in evidence that Charles would give you £800 for killing the old man?— I asked him where he would get £800, and he said his mother would give it to him. Mr. Kinkead: Was anything said about how you were to kill the father? — On the second occasion, there was no specification. It was just a matter of killing him. “

Eric Alchin also at Beau Pen Co. stated he witnessed the conversation between Reginald James Turk and Charles Ivan.

Harold Mahony, “At 9.30 a.m. on September 27, I received a ring at work. I recognised the voice as Charlie’s. ” He said, “‘Would you like to make £1000?’ I said, ‘What for?’ He said, ‘I cannot tell you over the ‘phone.’ He then asked me to see him outside he works at 2.30 p.m. He was not working at the factory at the time. When I saw him, I said to him, what’s the strength of this £1000? He said, ‘I want you to bump off the old man.’ I asked him what was wrong with his father, and he said, ‘There will be £1000 in it. It should be worthwhile doing it. I said, ‘How do you want me to do it?’ and he replied, ‘Go over to the Union Hotel, North Sydney, tomorrow night. Dad drinks there. Get close to him in the crowd, and when you reach for your beer you can slip a pellet of cyanide or arsenic in his beer.’ I said, You are making your first blue now, and he said, ‘What’s wrong with cyanide?’ I said. ‘If you used arsenic or cyanide they can trace it. They can dig up bodies and find traces of it.’ ‘ Mahony said he asked Charlie how he would recognise his father, and Le Gallien replied, “‘I will give you pictures of him.’ He said he would stay outside the hotel, as his father would recognise him. He said to me, There’s £1000 and a 1946 Chev. car in it. I asked him how did I know I would get it and he said, ‘I will give you a written guarantee; Mum will give it to you,’ ‘ Mahony said. “I told him I was not interested and did not want to have any part in it. I said I was not the type going around killing people. I said, why don’t you try Surry Hills or Redfern way? You’d be killed in the rush up there if you offered £1000, I then left him.“

Mr. Kinkead: “Didn’t you ask Charles to put up the price for his father’s murder from £800 to £1000?— No. Didn’t you take the conversation as a joke? — I knew Charlie was dead serious about it. Why didn’t you walk away? —You don’t get proposals like this every day. You say you were asked to kill a man? — Yes. It was a price for murder. Charles offered you £1000, but you wanted a car as well? — No, he said there will be £1000 and a car in it. I suggest he increase his offer from £1000 to £1000 and a motor car? — Yes. Did you ask him where the motor car was to come from?— I asked him and he said he would give me a written guarantee. His Mum would give it to him.“

Ross Le Gallien: – Mr Kinkead: “Your brother Charles was very devoted to his mother? — Yes. You knew the allowance your father made your mother had been interrupted on more than one occasion and on one particular occasion, he did not make an allowance for some considerable time?— That is correct. Did your father dismiss you and Harvey from the works after a fight at home on October 7, 1947?— He didn’t actually dismiss us. We just absented ourselves from the factory.“

Detective Inspector Ramus recounted the interview with Charles le Galien. “I was called into the room and Charles said to me, ‘I want to apologise for telling you lies this morning, I want to tell the truth. I don’t want a solicitor. I did see my father that day. I met him outside his office about 6.30 pm. I spoke to him for about five minutes and the phone rang, and he went inside and asked me to come in with him. I went inside with him and spoke to him for about an hour. I asked him for some money for Mum. He was writing figures on a piece of paper and told me how much it cost to keep Mum and us. The phone rang a couple of times and he answered it. He said, ‘ten minutes,’ ‘five minutes,’ ten minutes.’ All of a sudden he got wild and struck me across the face. I pulled out my pocket knife. I struggled with him and stabbed him. He fell down and was crawling about the floor. I got him a glass of water and gave him a drink. He told me he was all right and to go home. I took his coat and ran outside. I stood outside for about a minute and then ran down the lane and up a back street to Baden St. I put the knife in my back pocket, and at the Suspension Bridge, I put them down the drain. I half walked, and half ran across the bridge, up past the Northbridge pictures. I threw the wallet into a hollow. I ran across the golf links to Archbold Road, and I threw my father’s coat and a sweater into the bush. I then ran home, had a wash, and went to bed at 8 p.m.'”

After police evidence, Mr Kinkead said,’ “On my advice, my client will not give evidence before this inquiry.” The coroner then committed Charles Ivan Le Gallien for trial without bail.

The Trial

The Trial was held at Darlinghurst Court on Wednesday, November 24th, 1948. The public galleries were once again full of curious spectators. The jury was sworn in and Charles Ivan le Gallien pleaded ‘not guilty’ to the charge of murdering his father, Charles Louis le Gallien. Mr Kinkead remained as his defence councillor.

Day 1: The Crown prosecutor, Mr R. V. Rooney, K.C., gave his opening address, stating it was alleged the youth stabbed his father to death on September 30. Four young men would be called who would say that Charles suggested on various occasions that they should kill his father, trying to make it look like an accident and that he wanted to get the insurance. The defence, Mr Kinkead, stated that the accused acted in self-defence, that his father was a much bigger man and attacked him. The father was stabbed with the son’s pocket knife in the struggle that followed.

First to be called, Edith Grace de Groen gave evidence and was cross-examined by Mr Kinkead where it was heavily implied that she and le Galien were openly engaged in an affair.

Miss de Groen: “I had worked for le Gallien as a typist for 12 months in 1937. Mr. Kinkead: And since then, you have been his constant companion? — No. He set you up in a flat? — No. Gave you a gramophone?— No. A wireless set? — Yes. His association with you had been going on for eight or nine years? — No. I have known him many years. Have you been to Kiama on many occasions with the deceased as Mr and Mrs le Gallien? — No. Only this year. Did you go away with him in 1945 and 1946? — No. Do you remember an occasion when Mrs. le Gallien got into a car in which he and you were sitting? — Yes. We were driving to North Parramatta. Did you say, ‘Chuck the bitch out of the car, Charlie’? — I never opened my mouth. When was that? — About 1942. Was there anything between you and le Gallien between 1942 and 1943? — No.

Day 2: James Anthony Carroll, Allan McGill, Reginald Turk and Harold William Mahoney gave evidence that matched what they gave at the coronial inquest.

Day 3: On the third day, Charles Ivan told the story about the struggle with his father. He said that after asking his father for financial support for the family, the father replied that he was seeking a divorce to marry Betty de Groen. The next trouble had occurred at his home, le Gallien said. He had arranged with his mother to bring three friends home to sleep after a ball, because their own homes were too far away. When his father came home, said le Gallien, two girls were sleeping in his bedroom and he and a friend were preparing to sleep in the lounge room. “My father went into the bedroom and saw the girls. He returned and said, ‘Get those sluts out of here.’ He then went to my mother’s room and dragged her out of bed, took her to the kitchen, and began to abuse her. He rushed out of the kitchen and struck me on the chest. I recoiled and he struck me on the chest again, and then he took me out on the verandah and we fought it out there. He then dragged me to my mother’s bedroom. My mother was sitting on the bed crying.” Le Gallien said two of his ribs had been cracked in the fight and doctors strapped him up.

Le Gallien said his father worked out some figures and said how much it was costing a year to support the family. He said to his father, “You should provide for Mum, because she is your wife.” His father told him he was not going back home, because he would rather live with Betty de Groen. The boy added: “I said, ‘Mum is sick. You should provide for her, he replied, ‘Well, I am not’. I said, ‘Mum’s people started you off.’ He said, ‘Mind your own business. I am after a divorce. I have made a will and left everything to Betty de Groen’. When the phone rang, his father told him to get out and he replied, “I will not go until you give me the money.” His father said he would not give any money, rushed and hit him. At this stage, the young le Gallien broke down. He wiped tears from his eyes.

When he recovered, Mr. Kinkead showed the boy his penknife and asked how long it was since he had sharpened it. Sobbing, le Gallien said he sharpened it a few months ago. When his father attacked him he said “As you have attacked me I am going to protect myself.” His father threw him across his office desk and grabbed a penknife from him. Le Gallien broke down again and was given a glass of water by a sheriff’s officer. Recovering, he said he cut his hands while trying to get the knife back. He recovered the knife after a struggle, in which his father took him by the throat, nearly choking him. “I will kill you, you little bastard” The boy said he did not remember much more about the fight. He remembered his father on the floor crawling around. Mr. Kinkead: When he had you by the throat were you on the floor? — Yes. He was kneeling on me, holding me by the throat. Le Gallien said he had no idea how many times he had used the knife. Mr. Kinkead: When you went to the shop did you have any idea of harming your father? — No. I only went to get some money. When he attacked, what did you feel? — I didn’t feel safe. I thought my life was in danger. He had attacked me before. Le Gallien said that after his father crawled around the floor, he helped him into a sitting position on a chair alongside his desk. He gave his father his safari jacket to wipe blood from his wounds, and his father asked him for a glass of water. He washed his hands and brought back a glass of water. He asked his father if he wanted a doctor, but the father said he was all right, and told him to go home. Le Gallien said he wiped blood off his father and decided to borrow his father’s coat, into which he crammed his blood-stained safari jacket. He again asked his father if he wanted a doctor, but his father said, “I am all right. You go home.” Le Gallien said he left the office exhausted and sat down on a step until he recovered his breath. He then described how he had thrown away some of his blood-stained clothes and his father’s wallet before going home. Referring to conversations he had had with several youths on the subject of killing people, Le Gallien said one of them had mentioned how easy it would be to shoot a person with a rifle from a long distance. Le Gallien admitted having said jokingly: — “It’s a pity somebody doesn’t do that to my father.”

Charles Ivan Le Gallien was then cross-examined by the Crown Prosecutor (Mr. C. V. Rooney). Mr. Rooney: Did your father have any good points? — When he was sober he seemed quite decent to everyone, but he was very rarely sober whenever I saw him. When sober he was a good, kindly man? — Yes. Was he very generous? — I wouldn’t say that. Would you say he was a man who slaved and worked very hard and long hours? — I believe he worked hard in his earlier days. Did be keep members of the family in luxury? — He didn’t keep me for the past two years. Le Gallien said the home at Palm Beach was not luxurious and was not as good as their present home. He admitted that he and his brothers had attended the best schools and had been well-fed. Mr. Rooney: You have been trying to create the impression that there was want in your home? — No. Was your father very ambitious for you and your brothers and wanted you to do well like himself? — Yes, in a way. Le Gallien said that during the period his father was away from home he (the boy) had owned a motorbike. Mr. Rooney: Your brother had a car? — I don’t know. He has now a 1940 Chevrolet? — Yes. And an aeroplane? — Yes. Le Gallien told Mr. Rooney that his father had suggested that the family was extravagant. Mr. Rooney: Did your father show you that your mother was getting the equivalent of £24 a week1, tax-free? — Yes, that’s the way he worked it out. Le Gallien said he had disputed his father’s suggestion that he and his brothers should pay Mrs. le Gallien £2/10/- a week board. The boy had suggested 25/- or 30/- a week. He said that the terms of sale for the motorbike he bought for £200 had been a £70 deposit and payments of £8 a month, spread over two years.

Richard le Gallien purchased a Tiger Moth in October 1947.

At the time, he had been earning between £3 and £4 a week, Mr. Justice Herron: Do you really think that you were competent to discuss financial matters with your father that night? — I didn’t intend to, sir. Mr. Rooney: Will you agree that for the past two years, you and your brothers have been living in luxury? — We have been living comfortably. You had tastes out of all proportion to your age and income? — No, sir. Every penny you earned was spent on your own amusement? — Everything except my board. I suggest your father was forbearing and forgiving as far as his sons were concerned and didn’t thrash you? — He didn’t thrash us. He used to hit us, sir. Referred to the fight at his home, le Gallien said he did not consider himself more than a match for his father, whether the father was drunk or sober. Mr. Rooney: That night you cleaned your father up properly? — No, sir. You punched him into submission? — I didn’t consider it that way. You hadn’t a mark on you, did you? — The police could not have looked very well, sir. Closely pressed by Mr. Rooney, le Gallien denied having offered money to youths to cause his father’s death. Le Gallien described how he concealed bloodstained clothing in the scrub, near Merlin Street, Roseville, and went home naked to the waist. Le Gallien said he did not tell the police the circumstances of his father’s death, because he was frightened. His father was buried on Saturday and he went to a show the following Monday. Mr Rooney emphasised to the jury that his father’s death did not interfere with his recreation.

Charles dumped the blood-stained clothing in ‘Little Digger Park’, Merlin Street, Roseville,

A detective holding the blood-stained jacket and penknife used as evidence.

Day 4: Mr. Kinkead (to Mrs le Gallien): What was his general condition over the last few years of his life with you? — Terrible. He was never sober. Mrs le Gallien said her husband had driven to Palm Beach with their dog and had come back without it. He had said; “I suddenly disliked the dog and threw it out of the car at the Royal Motor Yacht Club, Broken Bay, of which her husband was Vice-Commodore.” She told of a time they went for dinner at the yacht club and her husband had accused a fellow member, Mr Nicholls, of drinking his whiskey, punching him in the face, broking his glasses and throwing him over a table.

Cross-examined by Mr. Rooney, Mrs le Gallien said that when police questioned her after her husband’s death, she had told them that Ivan had been in bed until about 6 p.m., and had not left the house except to use a telephone nearby. She admitted to Mr Rooney that these statements had been “a tissue of lies” which she had told to help her son. Mrs le Gallien said that Ivan arrived home at about 10.30 p.m. on September 30, and called her into the bathroom. When her son had told her he had stabbed his father she had not thought to telephone her husband to find out how he was or to summon a doctor or police. She said that Ivan had washed his trousers and socks because they were bloodstained. Mr Rooney asked You knew where that came from? — I had a good idea. You knew that your husband had lost a quantity of blood? — Yes.

Mrs. Le Gallien said her husband gave her a weekly allowance of £6/10/- or £7 and the boys each paid £1 board. You would say anything to help your son? — Yes. When the police arrived and said your husband was dead, was it a great shock to you? — It was. You knew he had been stabbed to death? — Yes. Will you deny the value of his life insurance policies was anything like £6000?— I don’t know. The Judge: Since he died, you haven’t made any inquiries as to what the estate was worth? — None whatever. Mrs le Gallien admitted that although it was two months since her husband had died, she, as sole beneficiary and executrix, did not know the value of the estate.

Day 5:

The Defence Addresses the Jury

Mr Kinkead told the jury to deal with the case as murder and not manslaughter and said that unless the jury was satisfied that the Crown had proved murder beyond reasonable doubt, it would have to acquit le Galiien. The Crown, in its opening address, had held up the dead man as a good fellow, he said. “If ever there was an example of a street angel and a house devil you have it in the evidence against le Galiien, snr.,” said Mr. Kinkead. Mr. Kinkead (to jury): Why do you think he took Miss Betty de Groen away for the week? Why does he take her to the beach — to sit on the beach and look at her in a bathing suit? For what other reason but that he is keeping her. I suggest le Galiien was treating his wife worse than he would treat a washerwoman.” The fact that there were several phone calls to le Gallien’s office during the interview with Charles indicated that the father was not afraid, said Mr. Kinkead. Also, the boy’s actions and movements in going to the office showed that he had not premeditated murder. There was no attempt to hide himself; in fact, the evidence shows he made it plain that he was there — pretty rotten preparations for a murder! “The fact that the boy only had a penknife on him shows that he was ill-equipped for a murder,” said Mr. Kinkead. Examination of the clothes belonging to the son and the father, he said, showed that the boy had taken off his safari jacket to staunch his father’s wounds, which proved that he aid not want him to die. Referring to the dead man’s wounds, Mr. Kinkead said the wounds on the neck could not have been received if the father was sitting on the office chair but could have been received in a struggle on the floor. Mr. Kinkead described le Galiien as an “unnatural husband” who had deserted them for someone else and expressed no love for them. If Mrs. le Galiien had started weeping when she heard her husband had died, she would have been a hypocrite, he said. “Yet nobody at home wanted the father to die, if for no other reason than they thought that everything would go to somebody else,” Mr. Kinkead said in conclusion. “They would be killing the goose that laid the golden egg.”

The Crown Addresses the Jury

Addressing the jury, Mr. Rooney said: “There is only one matter in dispute— the classification of the act which caused le Gallien’s death, and whether It was murder, manslaughter, or justifiable homicide, as suggested by the defence.” Mr. Rooney said that the defendant’s expressions in requests to four youths for someone to kill his father had gone from vague to specific as he increased his incentives. Mr Rooney said that talk of murder had started in a discussion between Ivan le Gallien and four youths, Harold William Mahony, Alan McGill, Eric Alchin, and Reginald James Turk, at the Beau Pen Company, in George Street. He said: “The talk went from the vague to the specific when le Gallien’s father was named and was still more specific when there was talk of £800 and a method of killing. Did it seem a joke if it was repeated month by month, with the offers increased? It was a joke to the youths, who did not take it seriously, but whether it was a joke on the part of le Gallien is different. The mind shrinks from horror at the thought that le Gallien had his mother’s authority The joke progressed from wishful thinking to direct action. Le Gallien was calling for tenders for the murder of his father. Mr Rooney said the original defence of an alibi had been abandoned. He added: In its place as a desperate resort, we have this theory of self-defence, and with it, this attack on Louis le Gallien’s character. It is remarkable that the whole attack on this man comes from the family. “Not one person outside the family has a word against him. “The family has alleged that le Gallien was a drunkard and a sluggard who lay in bed all day and had no regard or affection for his family. It has also been said that he left the home in destitution and in need of a few shillings. His wife has said she had no money for bread or meat. Do you think she was truthful, or was she trying to protect that unnatural son and would go to any lengths to do it? “After hearing the evidence, was there ever a more monstrous perversion of the truth? It gives me no pleasure to attack a youth or a woman, but I have listened to a dead man calumniated and vilified. He had every regard for his family and thereby signed his own death warrant.” Mr. Rooney said that le Gallien had provided generously for his family and had made a will leaving all his property to his wife. Le Gallien had left nothing to Miss de Groen. He added that at a fight at le Gallien’s home in November 1947, witnesses had stated that Ivan had punched his father only once. That was just as the police had walked in. Mr Rooney submitted to the jury that in the fight, le Gallien had “beaten his father into submission.”

Day 6: When the le Gallien murder trial was resumed yesterday morning, the senior Crown Prosecutor, Mr. C. V. Rooney, K.C., continued his address to the jury.

He said that, according to evidence given by Harold William Mahoney, Charles Ivan le Gallien urgently wanted his father’s death. If the jury accepted this evidence, they could only believe that le Gallien was longing for his father’s death for months, Mr. Rooney said. They could only believe that he had made a desperate proposal to somebody else to do the dirty work, so that his precious skin would not be jeopardised. Referring to evidence given by Richard Ross le Gallien, eldest son of the deceased, Mr. Rooney said he had been informed that this witness showed some emotion at the news of his father’s death, whereas other members of the family had shown none.

“If any of you are Shakespearean students, when Ross went into that box you must have been reminded of the tragedy of King Lear. The way he gave his evidence, exaggerated, and stabbed this man who had already died by stab wounds, must have given you an unfavourable impression of him. What sort of emotion did he show? Was it pity or triumph?”

Mr Rooney said the tragedy on September 30 was preceded by a feature that was unique, or very nearly so, in the experience of the Australian courts. The dead man had apprehended death. By telephone, he had countermanded previous instructions to Miss de Groen to bring dinner to his office and gave her fresh instructions. “I put it to you that for some reason the dead man apprehended foul play,” Mr. Rooney said to the jury. The defence had said that the ensuing events included a desperate life-and-death struggle which lasted a quarter of an hour. Mr Rooney suggested there was no struggle. Photographs of the small room taken after the tragedy showed only small signs of disruption. Referring to those photographs, Mr. Rooney said: “Can you say that it reflects a life and death struggle for 15 minutes? That struggle lasted possibly less than 15 seconds.”

“The Crown suggests that the dead man was attacked when leaning over the telephone, and possibly saying, ‘five,’ ” Mr. Rooney said. If le Gallien had acted only in self-defence, he would have not needed to fear the police or his father’s wrath, but, ignoring any instructions, to the contrary, would have gone to the hospital, the doctor, or the police. “You are asked to believe that when he proffered aid, his father refused it and said, ‘Get back home,’ “ said Mr. Rooney. “Well, his father may have been tired of life, but I don’t think he wanted death as badly as that. Instead, the youth left his father to die in that lonely office like a dog in a ditch.”

The Verdict

Mr Justice Herron told the jury he could relieve them from having to decide whether le Gallien Senior died as the result of wounds inflicted by le Gallien Junior. This was not denied by the defence.

His Honor said there had been a great deal said about domestic unhappiness in the le Gallien household. “We would probably agree that it was an extremely unhappy household,” he said. “But we are not concerned, as such, with the determination of whose responsibility that was. It was said that the deceased offered his wife what I suppose is considered the supreme insult of going off with another woman. I suppose it can be said that in the world today that is a common occurrence. However, this is not a court of morals, and we are not concerned with the rights or wrongs of it.” His Honor said nothing that ever happened in that household could have justified le Gallien Senior being killed.

The law was very jealous of human life, and it was not to be supposed for a moment that anything the deceased did in matrimonial offences deserved the taking of his life. Reviewing the evidence, his Honor said that if Mahony’s evidence were accepted, le Gallien was, in reality, plotting his father’s death shortly before it occurred, and this evidence would then take on a sinister aspect.

The jury retired at 1.22 p.m., returning at 3.12 p.m., with a verdict of guilty.

When Mr. Justice Herron received the verdict from the foreman of the jury, he told le Gallien he had been ably defended and in his view, had had a fair trial. “The jury have found you guilty, and the verdict was justified by the evidence,” his Honor said.

“I believe that you visited your father with malice in your heart because of his matrimonial offence, and without wishing to condone his infidelity, the penalty which you inflicted on him was the penalty of death, the one thing I am sure he did not deserve. I do not think your conduct can be justified or excused on account of your youth because a great many crimes in this city are committed by youths. This city seems to be besieged by juvenile gangsters, and they must be deterred.”

Charles Ivan le Gallien, 17, was sentenced to prison for life. He wept as the sentence was read out to him.

On Friday 12th of August 1960, Charles le Gallien was released from prison at age 29. Having only served eleven and a half years of his twenty-year (life) sentence. The NSW Minister of Justice Mr Mannix, said that le Gallien’s case had been reviewed and he was found to have been well-behaved, had studied hard and had learned carpentry. A psychiatric review determined his likelihood of rehabilitation to be high.