The note was pinned to the door of Henry Trevascus’ office at No 1. Glebe [Point] Road was written in shaky letters on a plain white business envelope. It read “Back on Friday Gone to Goulburn leave all letters at the shop.” The note has been stuck to the door since Tuesday 31st of October, 1911, and when the various visitors saw it they all left without putting too much thought into it. However, Henry’s daughter become suspicious on Saturday afternoon when she found the note was still up. She knew her father was not a man who spent many days away from his business. So, she and a boarder who lived in a room above Henry’s office acquired a spare key and opened the door. On entering the room, Alice Trevascus found her father lying face down in a pool of blood on the floor with his legs under his desk and head near the chair. The back of Henry’s head had been smashed open, and someone had cut his throat. The blood was everywhere. Henry Travascus had been brutally murdered.

Detectives searched the room for clues and found a faint bloody fingerprint on the note pinned to the door. Furthermore, on Henry’s desk was the coulter of a plough, a large sharpened piece of steel about 2ft long and 4in wide. Typically this item is used to turn the soil, though, in this circumstance, it was used as a weapon to strike the skull of Henry Trevascus, who was sleeping in his deck chair at the time. A Bengal razor was found on the desk, smeared with blood.

The motive appeared to be burglary; detectives came to this conclusion after Alice told them she had been with her father the night before the note appeared. He showed her £50 of banknotes that he had withdrawn from the bank to purchase some gold and platinum from a dentist based in Emu Plains who met him at the office the following day. Henry Trevascus was a metallurgist who traded in gold and precious metals. The £50 was missing. The detective then came across a letter on Henry’s desk that was from the Emu Plains dentist. He went by the name L. R. Fisher. He wrote that he had 8 ounces of gold to sell and would arrive at 8 pm on Monday. The press reported extensively on the murder of Henry Trevascus. Sensational stories were published with various theories as to what whodunit. Police asked L. R. Fisher to come for questioning. However, it soon became apparent that the dentist did not exist and was just a red herring.

By now, police sought after a new suspect, a young man who, on occasion, would visit Henry. On Tuesday morning, he asked the ground-floor shopkeeper if he could walk through the shop to access the stairs to Henry’s office. She agreed to let him through. Soon after, she heard a loud thud as though something heavy landed on the floor of Henry’s office above her. The young man rushed downstairs in an excited state, his body shaking. He said he fell down the stairs and hurt himself. He asked for a piece of brown paper she gave him, and he returned it upstairs. He left soon after, not to be seen again that day.

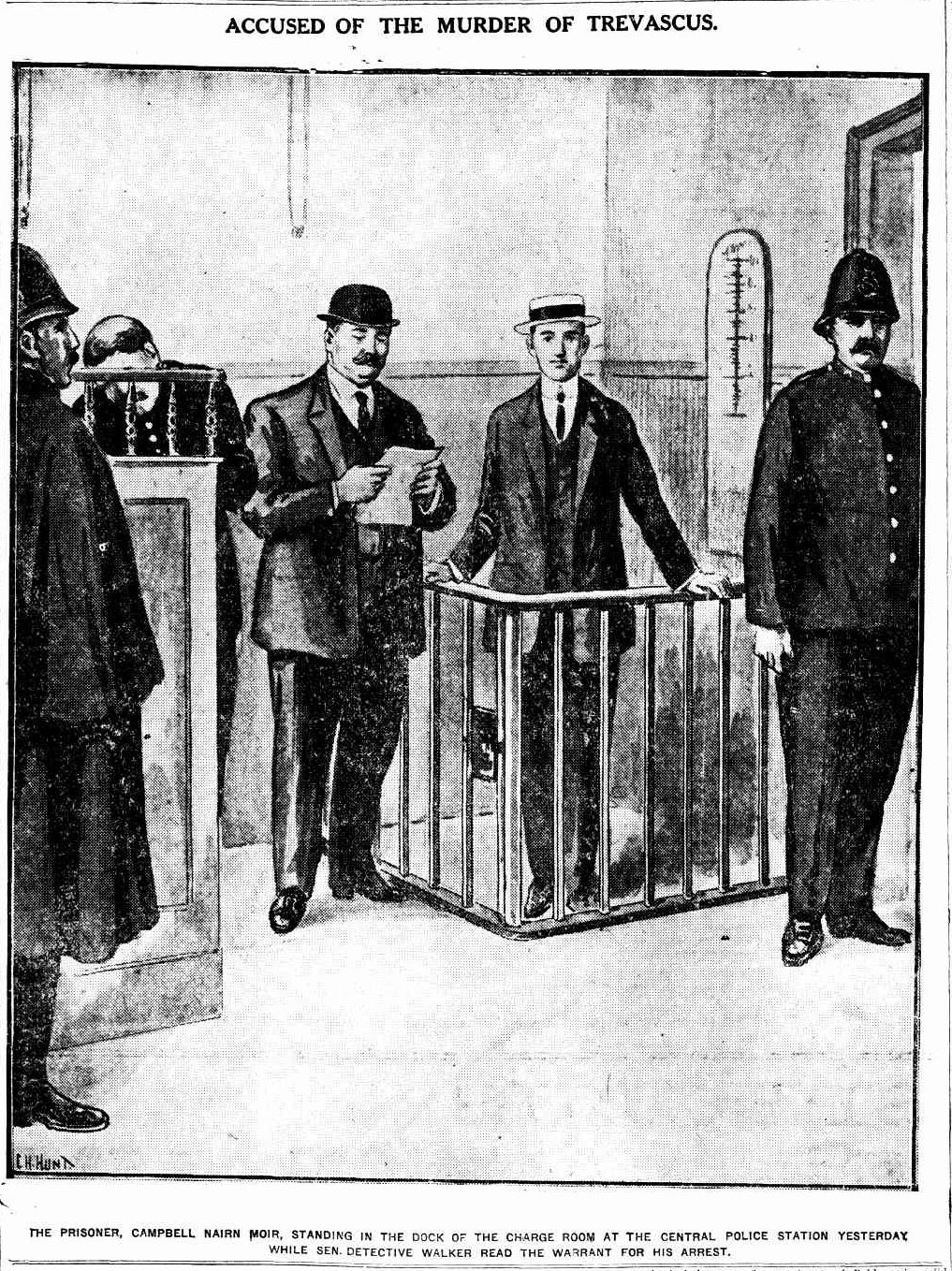

The young man was soon identified as a nineteen-year-old dental assistant, Campbell Nairn Moir. He was arrested in Melbourne and extradited to New South Wales, where he was met with hundreds of people at Central Station who came to see the suspect. According to police, Campbell was interviewed after the arrest and confessed to having known Henry Trevascus since 1910, even admitting to writing the letter from the fictitious Emu Plains dentist. His fingerprints were taken by detectives to be compared with those found on the note pinned to Henry’s door. Incredibly, it was revealed that Campbell was the nephew of a New South Wales government minister, Mr A. C. Carmichael. The public and press were concerned that Mr Carmichael may intervene on his nephew’s behalf and interfere with the course of justice. However, on the 24th of November, Mr Carmichael tendered his resignation as a member of the Labor Government.

Campbell Moir was identified as the young man who entered Henry’s office on the morning of the murder. At the coronial inquest, the downstairs shopkeeper pointed him out in court. Next, the fingerprint lab declared the bloody finger mark from the crime scene matched Campbell’s. By now, it was clear that Campbell was in serious trouble. On the second day of the inquest, he confessed to making plans to steal from Henry Trevascus but denied being responsible for the murder. Here he accused a Russian man of being his accomplice. He states that he sent the letter to Henry to trick him into withdrawing £50, which he could steal. After he was let into the terrace on Tuesday morning, his Russian accomplice followed him and was introduced to Henry as a friend of Campbell’s. However, when Henry turned around, the Russian struck him on the head, killing him instantly. Campbell says he left and waited across the road in the University Hotel for the Russian to appear with the £50. They took £25 each. At this moment, the Russian told Campbell he had also cut Henry’s throat.

The story of the Russian was not taken seriously, especially as a search for the man revealed no one and a Russian translator claimed the name given was not even of Russian origin. Campbell stood trial in January 1912; his defence argued he was not mentally sound. However, state medical practitioners reviewed him and said they found nothing wrong with him. Ultimately, the jury found him guilty of murder, and the judge passed down a sentence of death by hanging. However, lucky for Campbell, his sentence was commuted to life in prison, where he started at Darlinghurst gaol until it was closed in 1914, and he was relocated to Long Bay.

Glebe Road was renamed Glebe Point Road. The original building of No. 1 Glebe Point Road was demolished decades ago and was rebuilt as a multi-story complex that houses restaurants and an Anytime Fitness Gym. Another fantastic chapter in Glebe’s history.