The Sydney Hyde Park Murder

The murder of Vera Sterling in 1929 and the potential of her being the victim of an undetected serial killer.

By Elliot Lindsay

Men in grey suits and felt hats -detectives of the CIB- stood around a flower garden at the southern end of Hyde Park. To the onlookers passing through the neat and orderly gardens on their way to work, they must have resembled the hard-boiled detectives on the covers of crime fiction magazines – stern-faced, smoking and writing notes in black books. From a distance, it appeared they were all huddled around a bundle of old rags and newspapers amongst the lilies and shrubs of a triangular-shaped garden bed. They were partially correct. The old rags were the clothes loosely fitted to the lifeless body of a lady in her late forties, covered with a few pages of an old broadsheet newspaper for modesty. A collector of used bottles had discovered the poor woman while reaching for a discarded flask of methylated spirits. He noticed a pair of legs wearing dishevelled silk black stockings. At first, he presumed she was sleeping and felt embarrassed for creeping up on her as he did; however, a second glance unsettled him further. The woman’s wrists were bound together with what appeared to be a silk stocking; her face was a pale shade of blue.

The victim was identified as Vera Sterling, a 47-year-old woman well-known by police and locals of the Hyde Park area. Detectives determined she met her doom at approximately midnight on Thursday 21st of March 1929. However, the events leading to her final breath remained a mystery. Vera was heavily addicted to alcohol and was regularly spotted consuming methylated spirits. Police had arrested her on more than one occasion, and she had spent over thirty short stints in prison over ten years. Her face was blue, her eyes open and bloodshot. She bore light bruising around the neck that indicated strangulation. The coroner attended the crime scene to collect details to assist with the eventual inquest into her death. He determined Vera had been either strangled or suffocated until she died. However, it was the bound wrists that captured the imagination of police, the media and the public at large due to her arms appearing to have been physically manipulated to sit over her breast in the shape of a crucifix.

Furthermore, the tan-coloured stocking was tied with an elegant bow. Why would the killer take the time to tie a bow? Detectives were perplexed, though they speculated it could explain why they found no evidence of a struggle.

Very briefly, at the start of the investigation, it was thought that perhaps a man with sadistic tendencies had murdered Vera as part of a sex crime. Theories circulated she had been bound and strangled by a frenzied maniac but had been interrupted before finishing his vile deeds and thus fled the scene. Early interviews of potential witnesses even revealed Vera had been walking with a man around Darlinghurst earlier in the day. Could he have been the killer? The man was soon identified, and the authorities brought him in for questioning; however, he was released shortly after and dropped from the suspect list. Now, running out of leads, investigators changed tack and took the investigation down a different path. It was reported in the press that police were now hunting a female killer.

Detectives of the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB) of the New South Wales Police were baffled that no one could recall seeing Vera with a potential suspect in a part of Hyde Park that was well known to be popular with night-working prostitutes. Were they hiding something?

The CIB was now convinced that Vera was murdered by a fellow prostitute who had a vendetta against her. They came to this conclusion based on simple deduction. Firstly, the coroner did not find any evidence of sexual assault and ruled out a sex crime. Next, Vera was bound with a stocking; men didn’t wear stockings and were a man to use a stocking to secure someone; he would have simply ripped it off the victim’s leg. The stocking was tied in a neat bow, something a man would never bother doing. The stocking was tan-coloured, and Vera wore black stockings. Had a man strangled Vera, his strong hands would have left a deep, dark bruise, but the bruise was light and, therefore, likely made by a woman’s dainty hands. Finally, Vera was drunk and feeble; no man would have needed to tie her up before assaulting and killing her; he could easily have overpowered her in such a state. Ipso facto, police were convinced the killer could only have been a woman.

The ‘female killer’ theory quickly began to unravel as detectives interviewed the working girls of Sydney. Firstly, the assumption that she was a prostitute was challenged as, piece by piece, they learned of Vera’s past. Many of the sex workers who knew Vera said she was “of a different class” to them, a “cultured dame” who, when not intoxicated, spoke in an elegant and refined way. She would talk with the other girls but did not consider herself one of them and thus kept her distance. It was widely agreed upon that Vera had been born into a very wealthy English family who had commercial interests in New Zealand. She had been married to a prominent sea captain and lived an affluent life until falling on hard times. She never told anyone what had happened or where her husband had gone. She eventually became addicted to alcohol and went down a dark spiral of despair and dereliction. No one seemed to know any more than that. But was she even a vagrant? By definition, a vagrant is someone unable to prove a legal means of income. The interviewed sex workers said that although Vera didn’t work for her money, they were all under the impression that her income was not from illegal means; rumours had circulated for more than a decade that she received regular large payments, some speculating it was from her estranged husband, others said it was from a family trust. Some said she would occasionally go missing for a few months, then return sober, beautifully dressed, and would have intelligent conversations with people. Still, after a few weeks, Vera would regress. Not a single person could think of a reason why anyone who knew her would kill her.

Detectives began to rethink the theory after a post-mortem determined that Vera’s stomach was saturated with methylated spirits and she had not died from strangulation but from asphyxiation. Strangulation results from blood flow being restricted from the brain, which the coroner found no indication of having occurred. However, she did show signs of cyanosis, the bluish discolouration of the skin resulting from lack of oxygen in the blood—a sign of asphyxia.

After interviewing dozens of people, police were losing confidence that they would find Vera’s killer. The prejudiced narrative projected on the case had essentially led police down a path further away from the killer. Had she just been a common prostitute who had been killed in a ‘cat fight’, it would have made the investigation so much simpler. However, the 1920s had turned out to be the most violent era in Australian history up to that moment, and the NSW Police had more than a dozen cold case murders in Sydney alone. Adding one more case to the list of failures was not just embarrassing; it was becoming scandalous. But what if Vera had not been murdered at all? What if her deviant lifestyle had caused her death? What if Vera had been stumbling around the park in a “besotted state”, fell into the flower bed, landing face down, and being so intoxicated on methylated spirits that she was unable to unbury her face from the soil and save her own life, thus dying from asphyxiation, precisely as the Coroner said she had. Incredibly, this became the new primary theory. But how could police reconcile it with Vera being found on her back with her wrists bound? Police stated that some unidentified person, having seen the dead woman in an undignified state, thought it charitable to turn her over onto her back. Then, as Truth newspaper put it, “some other derelict with a spark of religion still smouldering in spite of years of debauchery tied the dead woman’s hands in the shape of the cross.”

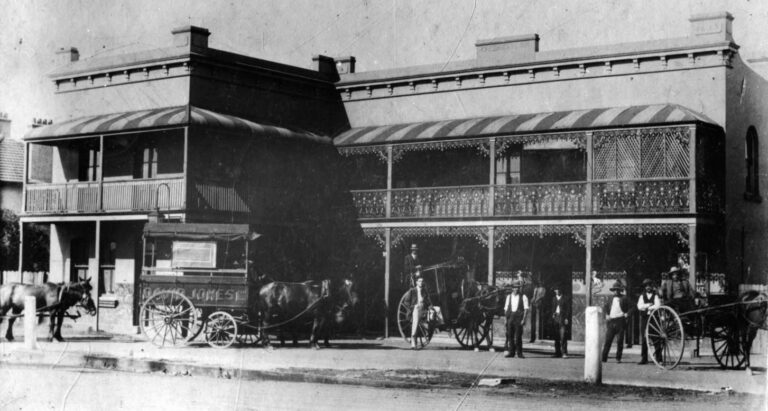

Lillian Carroll’s inmate file from 1923. She was found beaten in a vacant block on Kippax Street, Surry Hills, not long after Vera was found. Today the crime scene is a car park opposite the News Ltd building.

Officially, murder had not been ruled out, and although the case remained open, it was no longer the priority. Other murders had been committed that required investigation. In May 1929, an elderly homeless woman named Selina Stanley was murdered at a reserve in Erskineville. Then, in October 1929, Lillian Carroll was found nude and beaten in a vacant block on O’Loughlin Street, Surry Hills (see the crime scene on our Surry Hills walking tour). Drunk on methylated spirits, she later died in hospital. Some papers even reminded readers of Rebecca Anderson, who was last seen alive in Surry Hills and found murdered in a Long Bay reserve in 1924. Her body had been violated in a foul manner. The public was disturbed and questioned if the murders could be related to the Sterling Case in some way. Police dismissed the idea and stuck with the ‘death by accident’ theory. Some people wrote to the press accusing the police of losing interest in the case because Vera had been a homeless alcoholic. Had she been a woman of higher standing, the investigation would have been entirely different and not closed off with some ridiculous fantasy about religious symbolism. Authorities refuted the accusation.

Rebecca May Anderson was found brutally murdered at a reserve in Long Bay in 1924.

Only a few years after Vera’s death, the ANZAC Memorial was constructed, and Hyde Park was remodelled. The old flower garden, a cold reminder of that horrible crime, was cleared to make way for a footpath. With the visual reminder gone, her memory eventually faded away. Ninety-four years later, we still do not know who murdered Vera Sterling.

Want to learn more about the Vera Sterling case? Join the Darlinghurst: Sex, Scandal and Murder Walking Tour to visit the crime scene.