A long-forgotten murder mystery.

The forgotten story of a horrible unsolved murder in Sydney’s colonial North Shore.

The bottom of a well

On the morning of Monday the 22nd of September, 1862, on an estate located in Sydney’s North Shore, a lifeless male body was found at the bottom of a deep dark well. The throat of the man had a gaping wound, his arm lacerated. In his pocket was found a folded up pruning knife with traces of blood on the blade.

The Coroner

The man’s name was Andrew Bromley, a local 43 years old sawyer that had emigrated to the colony from Lincolnshire, England, nineteen years earlier. Initially, it was thought Bromley had committed suicide. Perhaps attempting with the blade and then finishing the job by throwing himself in the well to drown. Apparently, he had been depressed the days before due to a quarrel he had with his son. The city press, always hungry for a story, didn’t wait for the Coroner’s verdict and proceeded to print this unproven detail as fact. The City Coroner finally arrived and held a routine inquest at the local inn to determine the cause of death. However, the Coroner, perhaps assuming he was only attending the scene of an apparent suicide, came unprepared for a murder investigation. In the absence of a suicide note and having observed the neck wounds, the Coroner became doubtful that Bromley had taken his own life. He suspected foul play. The body had to be professionally examined by a medical practitioner. Time was of the essence as the body was in a state of decomposition. He ordered the body be transferred to the North Shore Police Station and examined by Dr Eichler and Dr Ward.

The post mortem

The two doctors conducted a thorough investigation of the body. Mr Bromley was found to have had three cuts to his throat, making a wound five inches in length. The first two cuts only penetrated the skin. However, the third cut was fatal, severing the lingual artery, the windpipe and the bone joining the tongue and larynx. A post mortem examination was next undertaken. From the appearance of the internal organs, the medical men believed the death took place before Mr Bromley’s immersion in the water.

The Great Fire of 1862

When Andrew Bromley was not working in the timber yards, he was employed as a labourer. On Friday the 19th of September, he was working for Mr Thomas Waterhouse, the publican of the Greengate Inn and owner of the Greengate estate. Bromley had come to help protect Mr Waterhouse’s orchard from a catastrophic bushfire that had been raging through the North Shore for several days. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the entire North Shore was a blaze, destroying many orchards, and homes and killing much livestock. The fire had finally reached the local area. All hands were required to subdue the fire before it overtook the local properties; already, it had devastated some neighbouring estates. Bromley joined in battling the blazes. At approximately 3 pm that afternoon, Bromley was noticed to be missing. Still, that evening he had not been seen, and he did not come home to his wife and nine children.

Unusual circumstances

By Saturday morning Bromely was still missing. This was out of character as Bromley was known to work to the last minute, then return directly home, walking through the door still red-faced, sweating and covered with dust. By Sunday, the community was alarmed and searched the Greengate estate where he was seen last. One of Mr Waterhouse’s sons, while walking across the property, found the hat that belonged to Andrew Bromley. Next, he found dried splatters of blood within three feet of each other. The following morning, Mr Waterhouse and Police Constable Dempsey commenced a detailed search, focusing on where the blood and hat were found. More blood was identified and observed to trail off some 240 yards towards a water well. The well was deep, holding 12 feet of water. Although no sign of Mr Bromley’s body was observed, the men decided to drag the well. Their suspicions proved to be correct as emerging from the depths came the waterlogged corpse of Andrew Bromley.

Murder was the case

The doctors presented their evidence at the Coroner’s court held at North Shore Police Station. They testified that the wounds would have resulted in death from blood loss within minutes. Hence, the ability of Mr Bromley to cut his own throat, close the knife, place it into his pocket, and then stumble 270 yards to the water well was near impossible. Witnesses were heard and cross-examined. The jury finally returned the verdict: – “we find that the deceased Andrew Bromley came by his death from wounds, chiefly from one inflicted in his throat. We have no evidence before us to show how his body got into the well, and that great suspicion and mystery attaches to this man’s death.”

Thus, suicide was ruled out.

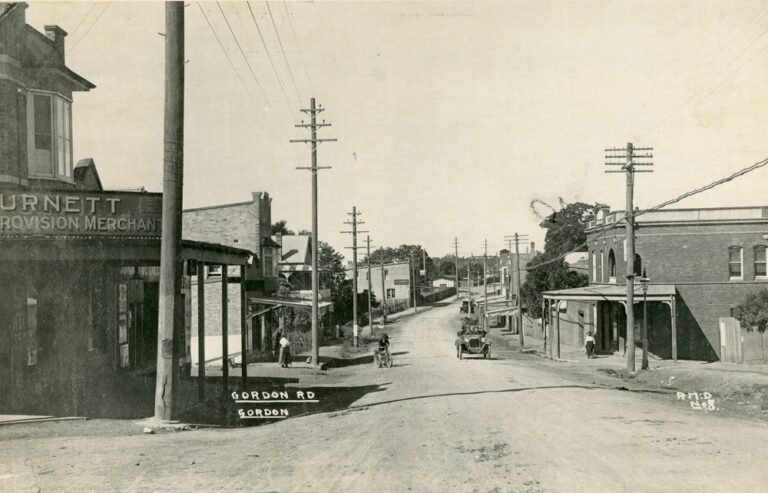

Colonial North Shore

With the community in a state of panic from the threat of fire and everyone’s attention being focused on it, the perfect opportunity arose for a person to take Andrew Bromley’s life. Unfortunately, we have no records regarding the life of Andrew Bromley. It appears he arrived in the colony nineteen years earlier. However, was he a gambler? A drinker? Did he have enemies? We do not know. What we do know is in the 1860s, Killara was essentially a wild rural frontier outpost that was far from being the gentlemanly suburb it eventually became. Thomas Waterhouse’s Greengate Inn was famous for being a favourite with the colony’s bare-knuckle boxing scene. Hard, violent men were drawn to his inn from all over to compete in, watch, and bet on fights held in secret isolated locations along the Lane Cove River. Waterhouse himself was involved in several organised fights and arrested many times. This kind of amateur boxing was illegal. Today, most people are familiar with the ‘push’ and ‘larrikin’ gangs who terrorised the Rocks, Surry Hills and Darlinghurst in those days. However, few people know that the North Shore was just as wild, with land-owning families engaging in violent feuds with one another. Therefore, the list of dangerous men with a predilection for violence loitering around the inn may have been quite extensive in 1862.

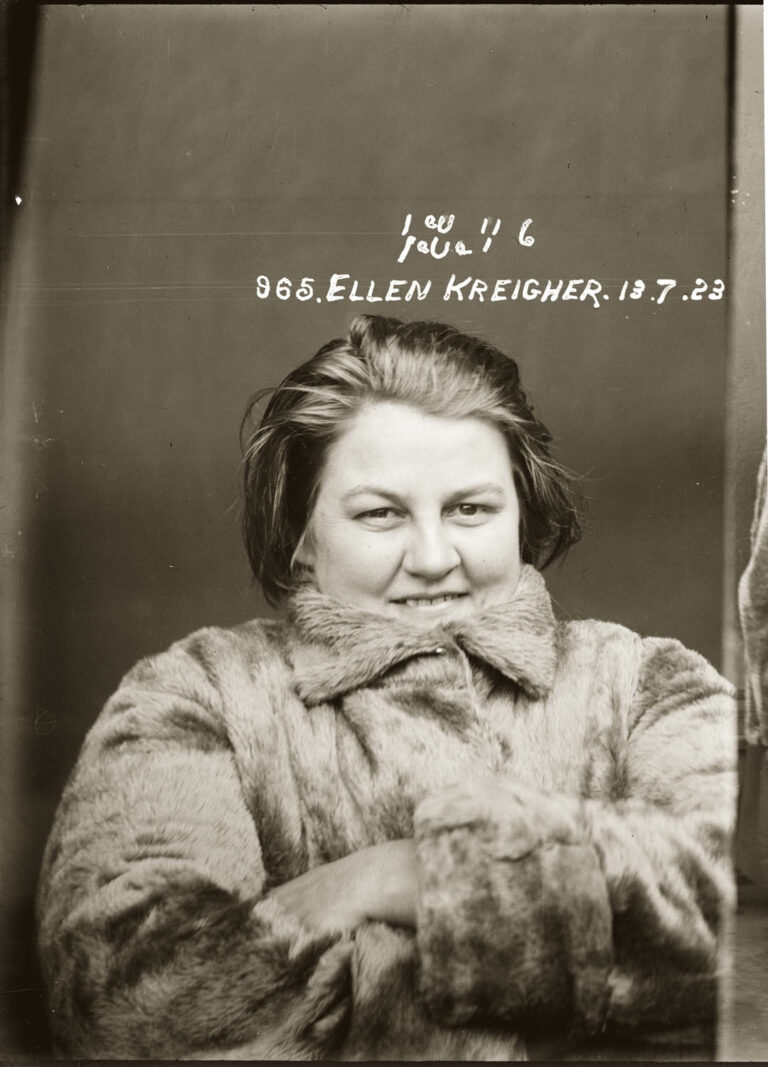

A suspect is named

On Friday 26th of September, law enforcement had a suspect. They brought him before the Water Police Court on Phillip Street, Sydney.

Joseph Bromley, aged 17, was arrested on suspicion of murdering his father. The men had been quarrelling over a disagreement in the weeks prior; the police decided to investigate. Upon inspecting the property where Joseph was employed, they found clothes he had allegedly worn on the day his father went missing. Suspicious bloodstains were found on the clothes, prompting the police to presume the worst. They arrested Joseph, and the court held him in remand. The press was quick to report him as a suspect. Lucky for Joseph, witnesses gave evidence that he and Andrew had reconciled soon after the quarrel and were on good terms. The blood-stained clothing was also accounted for by corroborating evidence; Joesph had been bleeding from the nose. His clothing was used to staunch the flow. The citizens of Lane Cove were enraged by the treatment of Joseph Bromley. Some wrote letters to the editors of the press accusing the colonial government of malpractice.

Robert Leal?

Meanwhile, as Joseph was being detained, another suspect was identified, a local man named Robert Leal. When Andrew Bromley did not return home on the night of the fires, his wife, Sarah, went to the Travellers Rest Inn (859 Pacific Highway Pymble) to inquire if anyone had seen him. Robert Leal was drinking at the inn and told Sarah, “I don’t think you will ever see him again alive; perhaps he’s got in the fire.” One Sarahy asked him what he meant, the drunk Leal said “Mind your own business; your husband is dead!”

The Sydney Morning Herald reported this encounter. Leal was questioned the following day and stated ‘he had not the slightest recollection of ever having made any remarks about the deceased to that effect’. Unfortunately, there is no reference to Robert Leal again.

However, it is worth mentioning that on the 5th of October 1860, Robert Leal’s wife, Louisa was burned alive in her own home. The coronial inquest could not determine how she came to be on fire. Furthermore, the Travellers Rest Inn was owned by Owen McMahon, the patriarch of the McMahon family who had been engaged in a blood feud with the Waterhouse family for over a decade.

A community outraged

In more ways than one, the people of Lane Cove were disturbed by the events surrounding Bromley’s death. First and foremost, the grief surrounding the murder of a prominent member of the small community. But what also disturbed the residents was how the case was treated. Incompetence from beginning to end. The Coroner choosing to hold the court nine miles away from the crime scene was considered somewhat unusual. Until not long ago, the coroners’ court proceedings would occur in a hotel or inn near the event within hours of the body being found. The reasons for this being there were limited ways to preserve cadavers; the evidence could be reviewed first-hand by the Coroner and jury while it was fresh; witnesses could be easily summonsed without needing to travel great distances, and all the facts could be elicited. Had this occurred, Sarah Bromley’s evidence could have been introduced sooner. The mysterious Leal could have been called to account for his whereabouts on the day. And Joseph Bromley would have been cleared of suspicion immediately instead of being detained in remand for seven days. A petition was signed by 124 residents. It demanded an inquest into the handling of the case and was presented to the Colonial Secretary. What came of the petition is unclear. However, the government did offer a reward for any information leading to the arrest of the murderer. Unfortunately, the murderer was never apprehended, and the case remains unsolved.

A Cold Case

We will never know what happened on that strange day in 1862 when fire raged along Lane Cove Road. The incredible chain of events that provided someone with the opportunity to commit such a brazen act of murder in daylight is quite astounding. Furthermore, the murderer had the time to drag the corpse to a well. Then the question arises, what did Robert Leal know? Was he the murderer? Was the murder related to the Waterhouse v McMahon blood feud? We will never know the answer.

Where was the well?

The well was described as being on the Greengate Estate. Wells are holes that are bored into the ground to tap into the subterranean water table and are typically located in depressions in the topography where water accumulates between bedrock and the ground surface. When observing a topographic map of the old Greengate Estate we can see an area suitable for a well.

The blue dot on the map below is positioned in a depression on the landscape. The arrow runs along a ‘draw’ in the contours indicating a drainage channel in the topography. It is likely that over the years, water has pooled in this depression and soaked into the soil, accumulating above the bedrock much deeper down. This has created a much higher water table which could be taped.

Further evidence is found in the Greengate Estate subdivision map of 1925 that shows a ‘drainage easement’ installed between Lots 21 and 16. Such an easement is only required to drain accumulated water.

Hence, it appears that the well was located in Lot 16 which today is the backyard of 10 Greengate Road, Killara. There is a high likelihood that the backfilled brick or stone-lined well still exists on the property somewhere.

A forgotten story from a forgotten era

Bromley Avenue, Pymble and a lonely headstone on the grounds of the St Thomas Church of England Cemetery, Willoughby, are all that remain of the memory of poor Andrew Bromley. His murder was forgotten over the decades. Today, Thomas Waterhouse’s Greengate Inn is known as The Killara Greengate Hotel. The orchards are long gone, the well since buried and many owners of the hotel have come and gone. In 1946, the old Green Gate Inn was demolished and rebuilt as a grand brick structure, although ye old green gate from the 1830s still hangs above the fireplace in the hotel. So if you ever find yourself in Killara Greengate Hotel, spare a thought for poor Andrew Bromley and have a drink in his memory.

By Elliot Lindsay, edited 2024.