By Elliot Lindsay

Murder in Newtown: When the gold rush and the wild west came to Sydney

There is gold in Newtown!

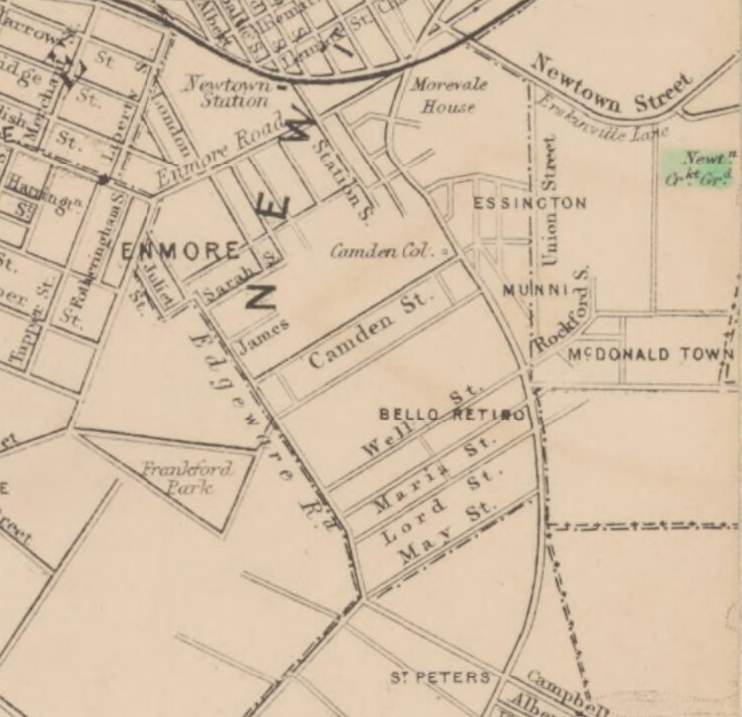

Thursday, 4 November 1852, a local landholder, Mr D. Cooper, claimed to have found gold while panning in Johnstons Creek (today, the creek is buried under Bedford Street). Cooper took several nuggets into town for all to see, triggering a gold rush. By Saturday, the hotels were filled with hundreds of strangers from across the colony.

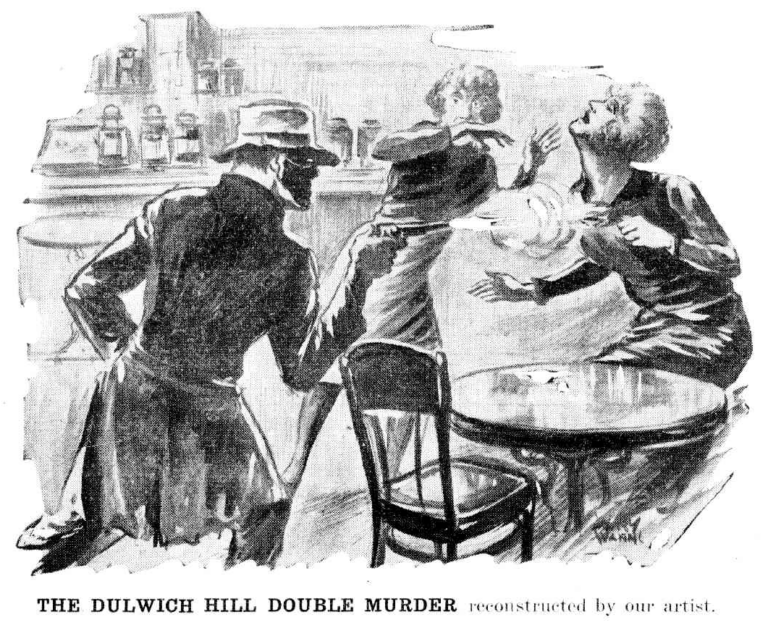

The following morning, amongst all the excitement of gold, while travelling along Bowen’s Lane (today known as Camden Street), local man John Hunt spotted what appeared to be a human figure tucked away in some scrub at the intersection with Newtown Road (Kings Street). Upon investigating, John discovered a local man he knew well, Mr William Hall. Seventy-nine-year-old William lived just near John at the bottom of Bowen’s Lane. Covered in blood and bruises, someone had severely beaten him beyond recognition. William’s boots and trousers had been removed and scattered around him with the trouser pocket ripped off. John touched his bloodied face; the battered man murmured, “for God’s sake, George, don’t murder me quite”. “Hall, My good man, who has done this?” asked John. William, recognising the face before him, said, “God bless you.” Blood then gushed out of his mouth and nose as he drifted into a delirium.

Mutilation

John collected the blood-stained clothing and found a white fence pailing covered in blood and grey hair, matching William’s and then took him home before notifying the police. William lay in extreme agony, being tended to by his wife and a local doctor. His left cheek was very swollen with a laceration about 2 inches in length. His neck exhibited several marks of violence, similar to those in attempted strangulation cases. His ribs and breast bone were broken, and most bizarrely, his genitals had been cut open with a knife, leaving a four-inch wound.

Tragically, William Hall died on Monday 7 November before telling his story to the police. Now it was a murder investigation.

Coronial Inquest at the White Horse Inn

William’s body now had to be inspected by the coroner; however, in 1852, there were no formal mortuaries in colonial Sydney. Before refrigeration, the coldest room in any neighbourhood was the barrel cellar under the local hotel, so typically, bodies were stored there. Police took William Hall to the White Horse Inn on Newtown Road (21 King Street), and when the coroner arrived, William’s body was relocated to a suitable room. If the coroner had reason to believe the death resulted from foul play, which in this case he did, a post-mortem and autopsy would be carried out. Typically, this took place in the hotel.

The coroner for Sydney, Mr J. R. Brenan, assembled a jury on Wednesday, 10 November at the White Horse Inn to inquire into the circumstances connected with the death. All the witnesses and evidence were summonsed before the inquest to recount what they saw that fateful evening. The coroner determined that William Hall spent his Saturday evening drinking at the Newtown Inn on Newtown Road, not far from Bowens Lane. At approximately 9 pm, Hall left the Inn quite ‘tipsy.’ Before departing, he deposited six shillings with the hotel for safekeeping in case he lost it on the way home. At 11:30 pm, a witness observed William lying in a lane fifteen yards from the inn, accompanied by a little black dog. He was not seen again before he was attacked. The jury found a verdict of willful murder against some person or persons unknown.

Arrests are made

After the coroner’s inquest, police arrested several suspects and charged them with murdering William Hall. The Empire newspaper described them as follows.

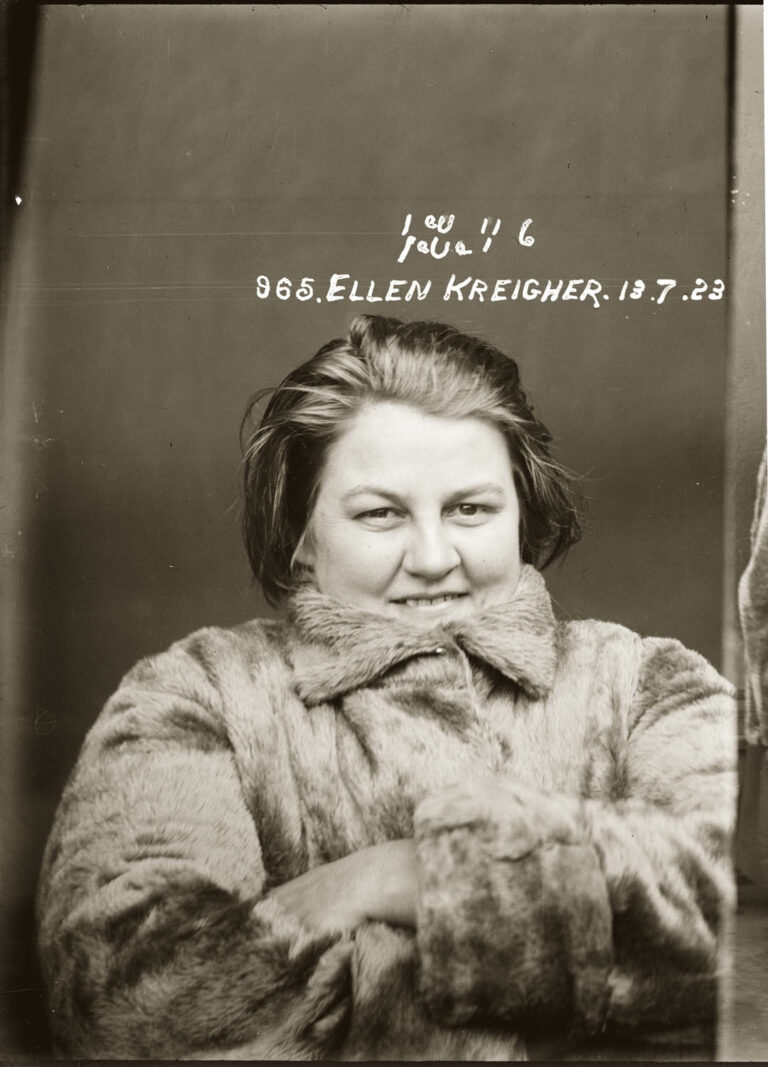

John Barker, a middle-aged man, in the garb of a labourer; George Woods, a young man, in apparent ill health, and very shabbily dressed; Mary Ralph, a female about forty years of age with an infant in her arms; Peter Dillon, a short, fat man, about thirty-five years of age; Ellen Rogers, a good looking, and a well educated young female, about nineteen years of age and Elizabeth Baker, a little old woman, apparently of weak intellect.

Each was now facing a sentence of death by hanging at Darlinghurst Prison if they could not prove their innocence.

These individuals had been seen intoxicated and quarrelling out front of St John’s Tavern (Horden and King Street, now Coopers Hotel). Then later, several of them, including George Woods, were observed walking down Bowen’s Lane, yelling at each other after midnight. Midnight is when the assault is believed to have happened. All the prisoners were arrested, cross-examined and confessed to being drunk on the evening and quarrelling in the lane. However, they all denied seeing William Hall. The suspects were brought before the magistrate where the case was dealt a fatal blow. It was determined the arresting officer did not give the suspects their legal rights before questioning. The defence pounced on this and demanded that all statements obtained be dismissed from court. Even though the victim had muttered the name ‘George’ which could very well have been George Woods, the magistrate agreed with the defence and had no choice but to acquit the defendants who were discharged.

Why was he mutilated?

No further suspects were brought forward after this, even when the Crown offered a reward of £25 ($10,000 in today’s money) for any information leading to the murderer’s successful prosecution. Sadly, the murder of William Hall remains a cold case almost 170 years on.

It is bizarre that the mugger decided to remove Hall’s trousers and use a knife to cut his genitals. Why would a mugger go to such lengths and risk being caught? The press and court do not seem to consider this unusual. Also, why did William feel it necessary to walk home without having possession of his valuables? Was it simply because there were hundreds of strangers in town due to the supposed discovery of gold, or perhaps, he had reason to anticipate the attack to come? It seems probable that if William was not murdered by George Woods, he was perhaps murdered by one of the gold-seeking strangers, but the press and police did not seem to make this connection. As a result, the murder of William Hall became another forgotten unsolved crime from Australia’s colonial past.

The Newtown gold hoax

So, what about this gold discovery? How come Newtown didn’t become another Bathurst? After prospectors dug several empty holes, the claim was discovered to be a hoax orchestrated by some local business owners. Incredibly, even though most saw through it early on, people continued digging well into January 1853. What a shame the community did not direct such stubborn perseverance into identifying William Hall’s killer.