By ELLIOT LINDSAY

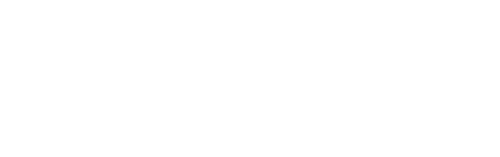

An artist’s impression of the 522 Marrickville Rd confectionary store shootings

Esther Vaughan operated the confectionary store that once occupied 522 Marrickville Road, Dulwich Hill. She sold confectionary and fruit to the local children for over 17 years and had watched the neighbourhood boys and girls grow into men and women.

Esther kept the store open later on Saturday nights; locals returning home from the theatres and dances would stop in for snacks. However, this particular Saturday night, 30 June 1928, was cold and quieter than usual. With her sister, Sarah Falvey, visiting, she decided to close up a bit earlier and prepare a simple supper for them both.

Then, at approximately 10:15 pm, the door creaked open. Cold air rushed into the warm store as the little bell above the door jingled, alerting the ladies to a late customer.

“Sorry, sir, we just closed for the day, but perhaps we can sell you something quickly, if you know what you are after.”

A tall young man entered and closed the door behind him. “I’m not here for chocolate,” he said as he drew a pistol from his pocket.

Across the road, sitting in his dining room, Alexander Ross was near finishing dinner when interrupted by two loud blasts fired within seconds of each other, immediately followed by blood-curdling screams.

Alarmed, he leapt from his chair and ran to his front door to investigate.

The lights were still on in the confectionery store across the road, however, the front door was closed. Fortuitously, his position allowed him a clear view inside the store. He observed what appeared to be a woman reclining over a chair and slowly sliding onto the floor.

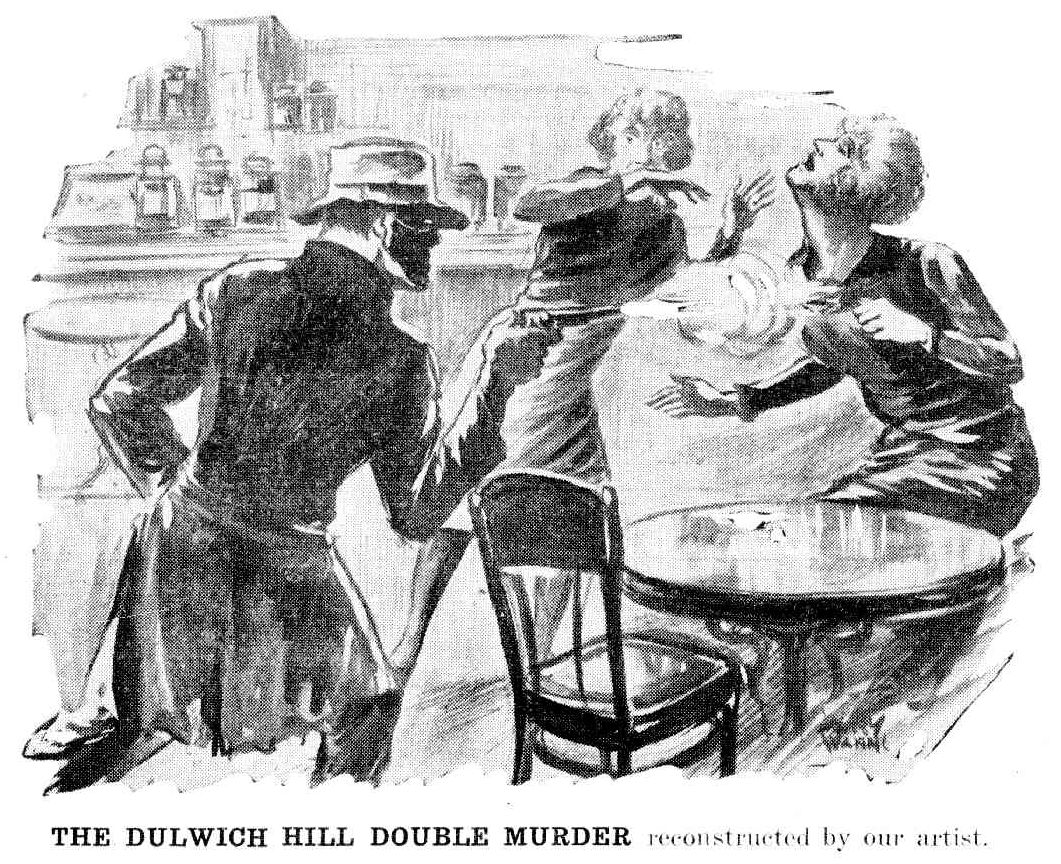

Suddenly, the door opened, and a tall, well-dressed man in a fedora, wearing a black mask and holding a pistol, came out. He placed the gun in his right hip pocket before peeling the mask from his face and throwing it onto the street. He very calmly walked up Marrickville road and turned at Durham street.

Identikit file illustration of the masked assailant

Alexander followed the man, from a distance, on the other side of the road. He saw the man pull his overcoat collar up around his neck before jumping onto a Harley Davidson motorcycle with a sidecar attached. Within moments he had sped away and was far out of sight.

Constance Campbell lived next door in a unit above 524 Marrickville road. She heard the shots fired and also listened to a man yell, “Open the door!” She was the first person at the crime scene after the man had left. Inside, Constance found Sarah Falvey half sitting in a chair. Constance asked her what had happened; Sarah simply pointed towards her sister lying on the floor in a pool of blood and replied, “she is shot.” When asked who did it, she replied, “a burglar.”

Constance saw the blood pooling under Sarah’s chair and then realised she was harbouring a bullet wound to the breast. Minutes later, Sarah was dead.

Esther, too, had been shot in the breast and was, miraculously, still alive. However, after she was taken to Marrickville Hospital Esther also tragically died, just minutes after arriving.

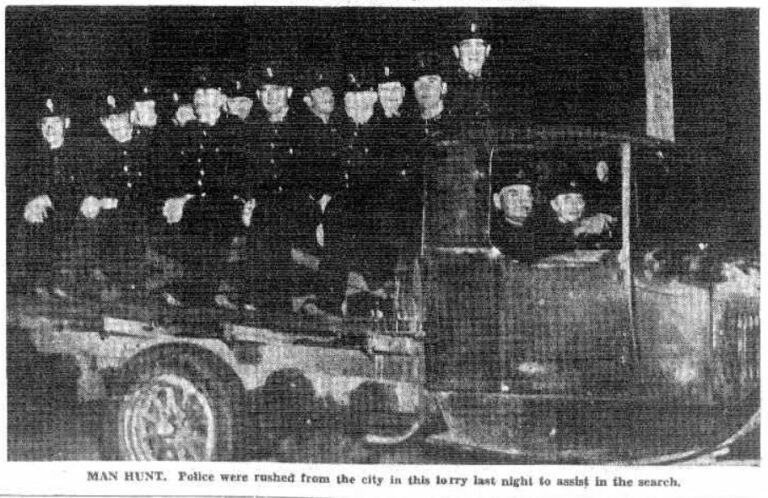

The Dulwich Hill Murder took the nation by storm. The murderer wearing a black bandit’s mask made it all seem like a pulp fiction crime thriller. The press exploited this and seized the public’s imagination with sensational and colourful investigation coverage, racing to see which paper could come up with the most attention-grabbing headlines and updates.

Detectives initially suspected the killings had resulted from a botched burglary. After all, what motive could there possibly be to kill two women in their fifties and sixties, if not theft?

However, cracks began to show in this theory.

The cash register remained untouched, and police even found several gold sovereigns hidden in various places around the store. With theft ruled out, the motive was unclear.

Theories

Newspapers started publishing articles claiming to have ‘exclusive access to police evidence’ or ‘secret police theories.’ One such theory that headlined the front page of the popular Truth newspaper went, ‘IS A WOMAN THE MASKED TERROR?’

Today we call this ‘clickbait’ as the article quickly dismissed its theory a few paragraphs in with reasons such as women don’t know how to ride motorcycles, and a woman would not have possessed the ability to aim the gun properly.

That the star witness identified the unmasked suspect as a man seemed not to matter.

Another theory was that the killer owed Esther money and wanted to ensure he did not have to pay it back. Esther’s family confirmed that she did lend money to people in need. Police questioned several suspected lendees, but all had legitimate alibis.

Some newspapers even commissioned authors to write fictionalised short stories recreating the murder, with speculated motives. Meanwhile, the New South Wales Government offered a £500 ($40,000 in today’s money) reward for information leading to the arrest and prosecution of the murderer.

A suspect

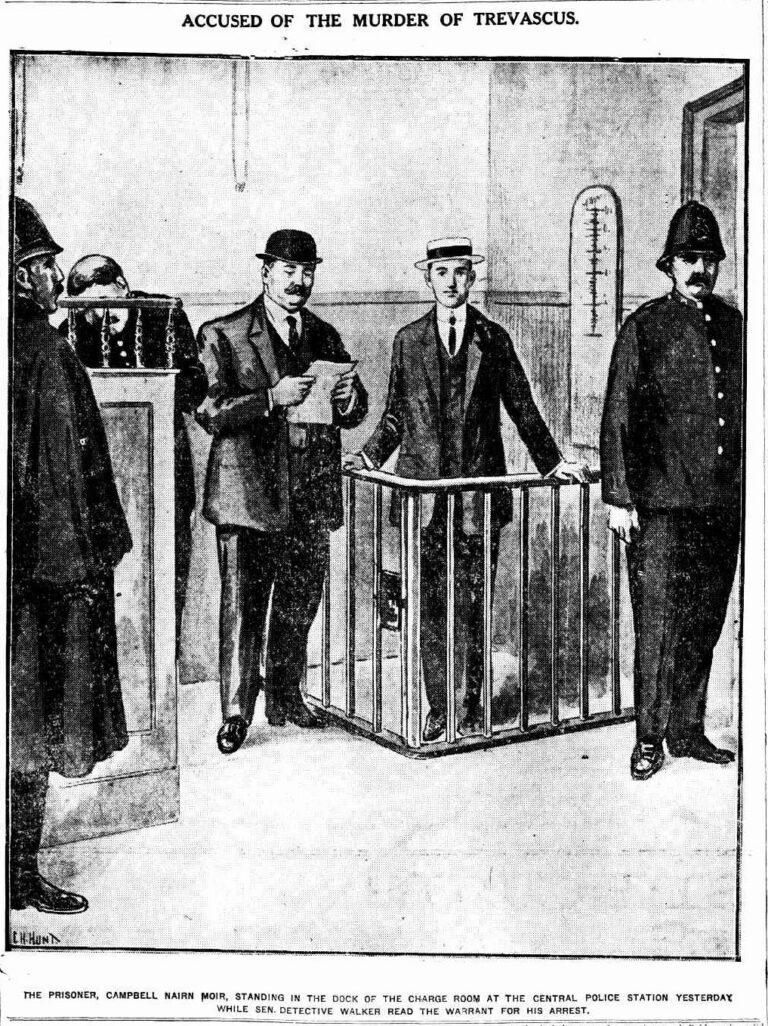

On 24 August, police arrested a credible suspect. An eighteen-year-old man named John Patrick Reynolds pretended to be a police officer to defraud businesses in the region. He targeted confectionary stores. When police arrested him, they noticed he matched the description given of the Dulwich Hill murderer.

From the night of the murder, Alexander Ross, the eyewitness who lived opposite, was called to observe a line-up of eleven men, including Reynolds. He identified Reynolds as the man he saw walking out of the store that night, and Reynolds was charged with the murder of Esther Vaughan and Sarah Falvey.

Daily Telegraph front page covering the murders, 28 Aug 1928

The Coronial Inquest

Reynolds was brought before a coronial inquest to determine if he was the probable killer. The coroner cross-examined the witnesses and reviewed the evidence. One witness claimed that Reynolds had boarded in her house, and she saw a revolver in his possession. She also stated that Reynolds told her to leave her husband and run away with him. When she said her husband would not allow that to happen, Reynolds said he would shoot the husband.

Reynolds claimed he was in Albury when the murder occurred and did not own a gun or even know how to ride a motorcycle. However, another witness contradicted the last statement.

But the shocking moment came when the star witness, Alexander Ross, was asked if Reynolds was the man he saw walking out of the confectionary store moments after the murder occurred. Ross asked Reynolds to turn around, which he did. Ross then said he could not be confident it was the same man. This admission was a significant blow to the prosecution’s case, and as a result, the Coroner announced that he could take the case no further. Reynolds was formally discharged and no longer a suspect.

The investigation continued for a decade, resulting in several men handing themselves to police custody, confessing to being the murderer. Each confession was discovered to be a hoax.

By the end of the 1930s, with no credible suspects, police archived the case, and over ninety years later, the crime remains unsolved. Some historians suspect Reynolds was the killer, but with all the witnesses long dead, it seems we will never learn the truth.

This article is from Neighbourhood Media https://www.neighbourhoodmedia.com.au/post/the-masked-killer-of-marrickville