Murder at 61 Ocean Street Woollahra

By Elliot Lindsay

The evening of September 8, 1884, was one of glamour and celebration at Como House, the grand Victorian mansion nestled at 61 Ocean Street, Woollahra. Como House stood as a testament to the wealth and high society at the peak of Sydney’s economic boom period with its elaborate parapet, detailed iron lace verandah, arched windows, and perfect gardens. Tonight, it was alive with laughter and the tinkling of glasses as Frances Ann Payne, a spirited and stylish widow, hosted a birthday party that promised to be the season’s social event.

At 39, Frances still possessed the youthful charm and vivacity that had marked her as a woman of great allure. With her captivating smile and a penchant for fashionable attire, she had carved out a place for herself in Sydney’s upper echelons, even amidst whispers and speculation about her personal life. Frances’s carefree demeanour masked a darker undercurrent that would soon surface as she mingled among her numerous guests—naval officers, financiers, and legal professionals.

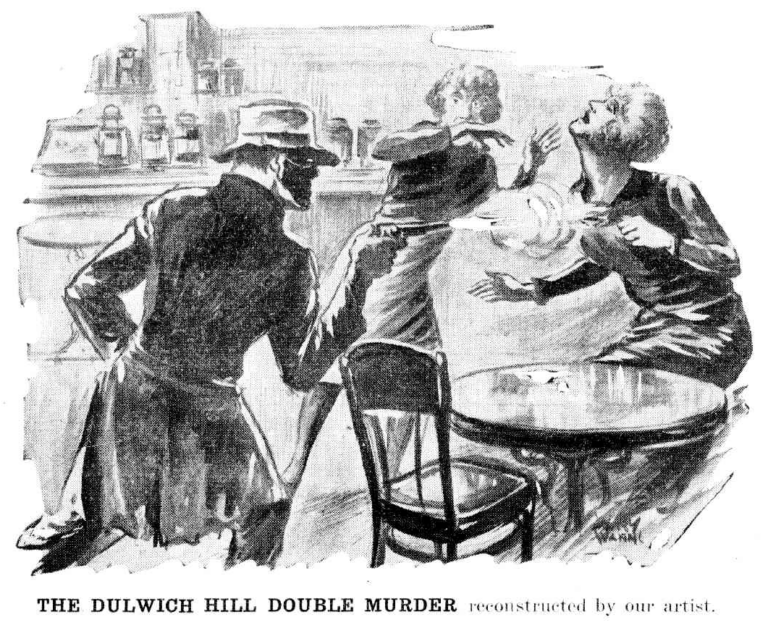

The festivities continued late into the night, with supper served in the elegantly decorated dining room. Frances was seen sipping on a glass of porter as she conversed with the few remaining guests, including Captain Osborne of H.M.S. Nelson, stockbroker Charles Long, and solicitor Joseph Marks, a man known to be particularly close to the widow. As midnight approached, the guests began to leave, with Charles Long bidding his farewell shortly before the clock struck twelve. Only Joseph Marks remained behind, as he frequently did, intending to spend the night at the mansion, though giving an excuse to the other guests that he missed the last ferry to the North Shore.

Around 1 a.m., the lights dimmed, and Frances retired to her bedroom, leaving Joseph in his adjoining guest room. The peace of the night was shattered just minutes later by a chilling cry. Marks rushed into Frances’s room to find her writhing in agony on the floor, her limbs stiff and her face contorted in pain. In a voice barely above a whisper, Frances managed to choke out, “I’ve taken poison… strychnine.”

Joseph, panicked and uncertain, reached for a nearby glass and, noticing an unusual bitterness on his tongue, hurriedly rinsed it out. He tried to force water down Frances’s throat, but her teeth were clenched in a rigid spasm. She gasped for breath, her body convulsing violently. He left her on the floor, writhing in agony as her body contorted and the bones in her back began to crack, to run next door to the residence of Dr. Nott. Dr. Nott ran with him back to the house to treat Frances, who was still breathing. He directed Joseph to race to a local chemist to acquire an antidote. Fifteen minutes later, he returned with the medicine, only to be greeted at the door by the doctor; Frances Ann Payne was dead.

The Beginnings: A Life of Wealth and Social Climbing

To unravel the mystery of Frances Payne’s death, it was necessary to examine her life—one marked by wealth, tragedy, and whispered scandals. Born Frances Ann Stanbrough in Islington, London, in 1845, she came from modest beginnings. Her family had emigrated to Australia when she was still young, and by the age of 19, Frances had caught the eye of William Payne, a man of significant means.

William Payne, a gentleman 24 years her senior, came from one of Melbourne’s most established families. Alongside his brothers, Thomas Budds Payne, who would become one of the wealthiest men in Australia, and John Payne, William had built a successful career in property and business. In 1864, the couple married in St. James’s Church, Melbourne, and soon after, they welcomed a son, William Thomas Payne, born in 1865.

William Payne’s wealth enabled the family to live in grand style. They settled in Malvern, where William constructed a large mansion named Emo, the epitome of luxury. However, in 1880, when William was only 59, he succumbed to heart disease. His death left Frances, then 35, with a vast estate to manage and the responsibility of raising their teenage son.

William’s will stipulated that Frances would inherit all his properties and wealth under certain conditions. The terms granted her a life interest in the estate, but with a crucial caveat: if she were to remarry, her income would revert to their son. The properties, worth an estimated £50,000 at the time, included several lucrative holdings and significant liquid assets. Frances’s life was transformed—she was now one of Melbourne’s wealthiest and most eligible widows.

Moving to Sydney and Whispers of Scandal

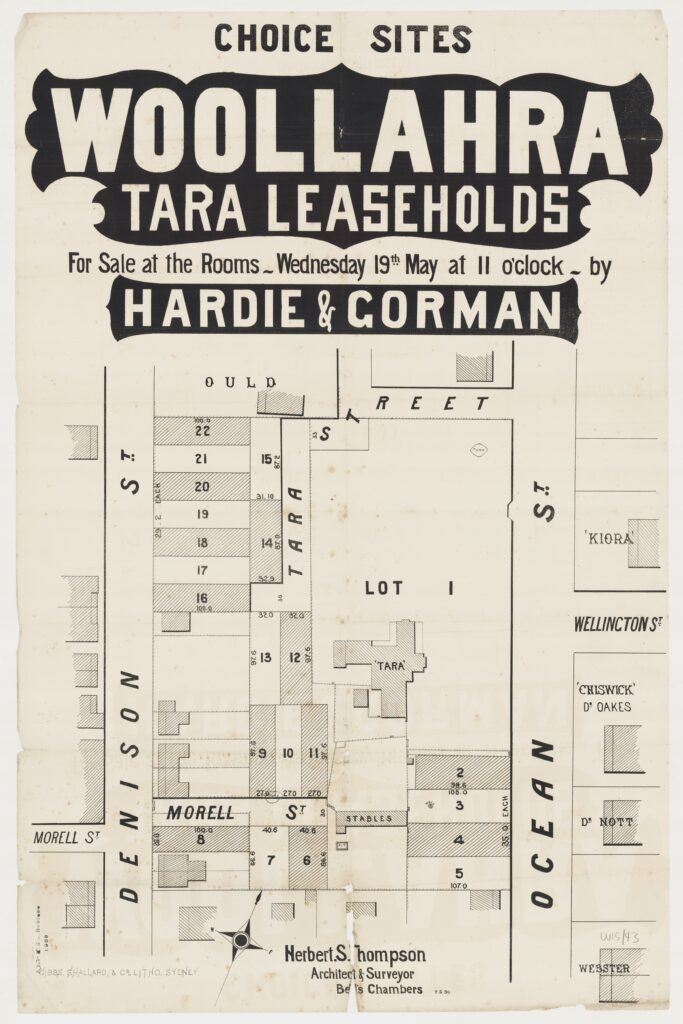

In 1883, Frances moved to Sydney, where she purchased the recently constructed Como House on Ocean Street, Woollahra. The Italianate mansion became the centre of her new life, where she hosted grand soirées—gatherings that were as much about displaying her wealth as they were about cementing her status in society. The tall, arched windows and sprawling gardens made for a picturesque setting, but there was something about the house that seemed to invite drama.

Despite her outward charm, Frances’s behaviour soon drew attention. There were rumours of affairs and even talk of a clandestine marriage, though no evidence ever substantiated these claims. Her frequent guest, Joseph Marks, was often seen in her company, prompting speculation about the true nature of their relationship. Their closeness was apparent, but whether it extended beyond friendship was a question that society was all too eager to gossip about.

The whispers grew louder following a sudden change in Frances’s social circle, with certain old friends falling out of favour and new acquaintances, such as the ambitious stockbroker Charles Long, frequently appearing at Como House. This shifting dynamic made some wonder whether Frances had become involved in complex financial dealings, using her wealth and influence to secure investments. But nothing concrete came to light, and the truth remained hidden behind the mansion’s closed doors.

The Inquest: A Death Shrouded in Suspicion

The morning after Frances’s death, news of the tragedy spread rapidly. The coroner was called, and an inquest was arranged at the Castlereagh Hotel, which in those days was located at 30 Moncur Street, Woollahra. The coroner, Mr. Shiel, presided over the proceedings, which drew a crowd of curious onlookers, press reporters, and those with a vested interest in the outcome. The inquiry quickly turned its focus to three possible explanations: suicide, accident, or murder.

Many found the idea of suicide implausible. Frances had seemed full of life on the night of her birthday, laughing with guests and making plans for the future. There were no known personal or financial troubles that would have driven her to such an extreme act. She had recently purchased a property at Point Piper on Wolesley Road facing Double Bay and was proudly discussing the plans for an opulent mansion she was to build and live in. Furthermore, her last conversation with Joseph Marks had been about planning a theatre outing for the coming weekend, hardly the thoughts of a woman contemplating taking her own life.

The possibility of accidental poisoning was considered next. The bottle of strychnine, which Frances had reportedly purchased months earlier to poison rats, could not be found. Its absence raised questions about whether it had been deliberately disposed of or if it had even existed in the first place. Marks testified that Frances was not in the habit of keeping dangerous substances within easy reach, and no evidence of strychnine was found elsewhere in the house.

As the examination continued, the spectre of murder grew larger. The inquest revealed that Frances had died from the effects of three grains of strychnine, a quantity far beyond what could be considered accidental. The poison had to have been administered in a concentrated dose, indicating a deliberate act. But by whom?

The Suspects: Love, Money, and Deception

Joseph Marks, who had stayed at the house on the night of the poisoning, found himself at the centre of the investigation. As Frances’s close companion, he had the opportunity to administer the poison. Moreover, his actions on the night of her death—rinsing out a glass that had tasted bitter—seemed suspicious. Was it possible that Joseph and Frances had been engaged in a secret relationship, one that he feared would come to light and disrupt his life? Or was there something else—something financial, perhaps—that made her death advantageous to him?

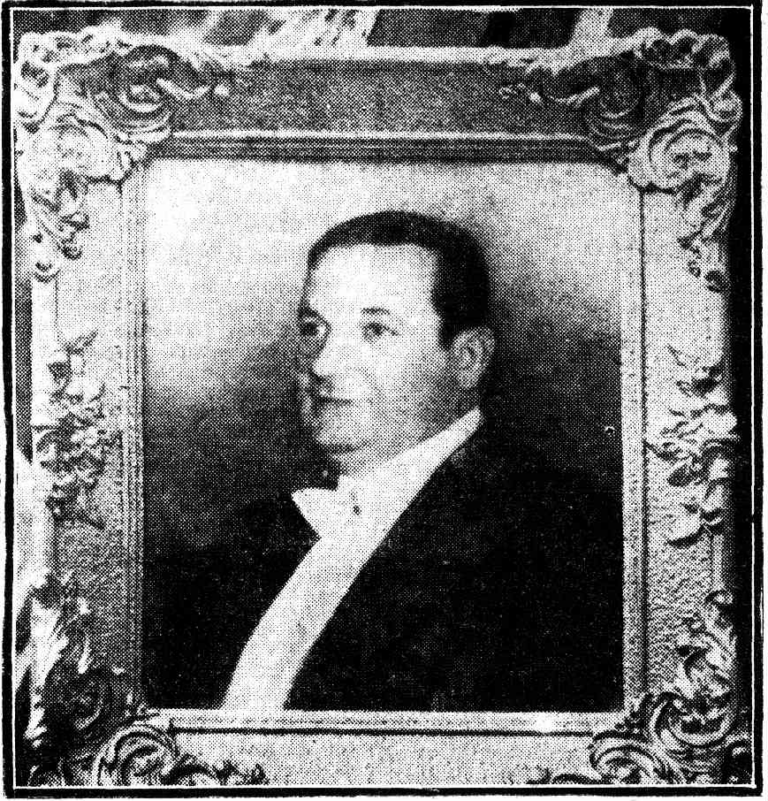

The stockbroker Charles Long also came under scrutiny. Long was a partner at Marks & Co., one of Australia’s oldest stockbroking firms, originally established in Melbourne in 1865 to finance gold mining operations. In 1883, the firm decided to expand into Sydney, selecting Long to establish its first branch as the resident partner. However, just three months after his arrival, he found himself embroiled in a scandal that would have undoubtedly caused great concern for his Melbourne directors. Marks & Co. later amalgamated with Citigroup in 1985.

Long had left the house just before midnight, yet his presence at the party—along with rumours of financial difficulties—fuelled speculation about his potential motives. Some suggested that Frances might have been involved in a financial scheme with him. His testimony at the inquest was vague and evasive, raising further doubts about his role in the unfolding tragedy.

Could the rumours have been true? Was he attempting to cover up a financial scandal that could jeopardise his firm’s standing in the Sydney market and his own future with Marks & Co.? Or were these whispers merely the fabrications of territorial Sydney stockbrokers, resentful of a Melbourne rival encroaching on their domain?

The Investigation: Secrets Uncovered

The coroner’s investigation extended beyond the immediate circumstances of Frances’s death, delving into her life in Sydney and her relationships with those around her. It emerged that, shortly after William Payne died in 1880, Frances had grown increasingly involved in high-risk financial ventures, some of which bordered on speculation. It was speculated that she had lent considerable sums of money to Charles Long, who was known to have suffered losses in the stock market. Was her generosity to Long born out of friendship, or was there more to their relationship?

Additionally, Frances’s social circle included prominent gentlemen and some individuals of questionable repute. The fact that Como House had hosted certain known gamblers and unscrupulous characters hinted at a possible underworld connection. Had Frances become entangled in debts or blackmail? The authorities could not determine whether this was linked to her death, but it painted a picture of a woman whose life was more complex and dangerous than it appeared on the surface.

A Scandal in Melbourne

After the death of her husband, William Payne, Frances Ann Payne exhibited a lively and vivacious lifestyle. She was in her mid-30s at the time, full of energy, and seemed determined to enjoy her newfound freedom. The Payne family home in Malvern, “Emo,” became the setting for many social gatherings. Frances hosted grand parties, inviting various acquaintances from Melbourne’s high society. Her behaviour during this time was considered by some to be extravagant and, at times, even scandalous for a recent widow who should be in mourning. There were rumours about her social circle and the nature of some relationships, which led to whispers among the more conservative members of the community.

Joseph Marks, a managing clerk for the prestigious “Norton & Smith Co.” solicitor’s firm, became a frequent guest at Emo. His involvement with Frances seemed to go beyond mere friendship, as he often stayed overnight at her home. Marks was a trusted figure in her life and was thought to have had a close relationship with her that may have extended into a romantic connection. He was around 14 years younger than Frances and, according to some accounts, was a companion who helped her cope with the loneliness that followed her husband’s death. Their interactions and his frequent presence at Emo fuelled gossip, particularly because it was considered inappropriate for a single man to be staying with a widow without the presence of other family members. The Payne family was enraged by Frances’s behaviour, and with the significant influence her brother-in-law, Thomas S. Payne, held over Melbournian high society, it did not take long for Frances to be shunned. It appears this was likely the motive for her moving to Sydney. Unlike Melbourne, Sydney had a reputation among Melbournians as being a city where money could gain your social acceptability. Thus, it was a place where she could live her life without the scrutiny of the powerful Thomas Payne.

There were also suggestions that Marks may have assisted Frances with managing her financial affairs. Her late husband’s will left her with a significant estate, but it also imposed certain restrictions that would impact her income if she were to remarry. This arrangement created an air of intrigue around Frances’s social activities and her relationship with Marks.

The nature of their association was later scrutinised during the inquest into Frances’s mysterious death, as Marks had been staying at her new residence, Como House in Woollahra, on the night of her poisoning. His involvement in her life after William Payne’s death and his presence on the night of her demise made him a person of interest in the inquiry.

The Woollahra Mystery

The coronial inquests into the death of Frances Ann Payne involved multiple sessions that sought to uncover the circumstances surrounding her sudden death from strychnine poisoning at her residence, Como House, in Woollahra. The media report on the investigation under the headline “The Woollahra Mystery.”

Initial Inquest – September 10, 1884

The first inquest began the day after Frances Payne died, in the Castlereagh Hotel, which in those days was located at 30 Moncur Street, Woollahra. It was immediately clear that she had died from strychnine poisoning. Witness testimony was gathered from Joseph Marks, a managing clerk who had been present at the house on the night of her death, as well as other witnesses, including medical professionals who had attended to her.

Joseph Marks’ Testimony: Marks recounted the events leading up to Payne’s death.

Medical Testimony: Dr. Nott, who lived nearby, was the first to arrive, followed by Dr. Collins. Both doctors described the symptoms consistent with strychnine poisoning. They performed a post-mortem examination, which confirmed the presence of strychnine crystals in her stomach.

The initial session concluded with uncertainty over whether the poisoning was accidental, suicidal, or deliberate, prompting further investigations. Frances was given a funeral and buried at Waverley Cemetery.

Continued Inquest Sessions – September 17, 1884

During the resumed inquest, new evidence emerged when Senior-Constable Blackman testified that he had found a small bottle labelled “Poison – Strychnine” in the garden outside Frances Payne’s bedroom window. This discovery raised more questions, as it suggested the bottle might have been thrown from the window.

Further testimonies were examined by witnesses:

Marks’ Further Testimony: Joseph Marks expanded on his account, stating that there had been no signs of depression or distress from Frances Payne that would suggest a motive for suicide. He maintained that Payne appeared to be in good spirits, discussing future plans such as attending the theater and a flower show.

Suspicious Circumstances: Marks mentioned that the tumbler used to give water to Payne had a bitter taste. No clear evidence could be found regarding how or when Frances ingested the poison, and no container for the strychnine was found in the bedroom initially.

Alfred Carter, Chemist: A chemist named Alfred Carter testified that he had sold Frances the strychnine in June, ostensibly for killing rats, but no container for the poison was found in the house during the early searches.

The Servants

Eva Cliff, a housemaid employed at Como House for five weeks before Frances Ann Payne’s death, provided key testimony about the household’s routine and Joseph Marks’ frequent presence. She stated that Marks often stayed overnight, only leaving for a few days on a supposed business trip to the Blue Mountains two weeks before Frances’s passing. Frances was accustomed to having breakfast in bed and rarely left her room in the mornings. On the night of her death, Cliff observed her in good spirits but did not see her retire to bed. The next morning, she found several bottles and glasses left on the dining table and was shocked to learn of Frances’s sudden demise, as she had not been aware of any disturbance during the night. She also revealed that Frances and the servants had unrestricted access to liquor stored in a cupboard under the stairs, which was never locked.

Mary O’Shea, a cook and laundress who had worked for Frances for 11 months before being replaced by Cliff, testified about Frances’s household dynamics and relationships. She confirmed that Joseph Marks had been staying at Como House nearly every night since returning from New Zealand with Frances, a shift from his previous routine of only staying three nights a week. She recalled that Frances had once handled strychnine, using it to poison rats, but had never seen her consume poison or discuss self-harm. When asked about other visitors, O’Shea stated that stockbroker Charles Long also visited frequently, though not as often as Marks. While she was unaware of any financial dealings between Frances and Long, she confirmed he was a regular guest at Como House.

The Horrifying Effects of Strychnine

The inquest into Frances Ann Payne’s death devoted significant attention to understanding strychnine, the poison that killed her, exploring its devastating effects and the speed with which it acted. Medical witnesses, including Dr. Nott and Dr. Collins, described how strychnine attacks the nervous system, triggering violent convulsions, intense muscle contractions, and an arched back as the body succumbs to spasms. Dr. Nott, arriving first, noted Frances’s rigid limbs and clenched jaw, while Dr. Collins explained that death typically results from asphyxia, as the diaphragm and chest muscles lock, halting breath. A pharmaceutical expert revealed that just half a grain could kill, yet Frances had ingested nearly three grains—a massive, deliberate dose. The timeline puzzled investigators: symptoms emerge within 15 minutes, with death following between 30 minutes and two hours, suggesting the poison struck her after retiring, though whether it came via supper, a drink, or later remained unclear.

Further scrutiny centered on strychnine’s intensely bitter taste and how it might have been concealed, raising questions about its administration. Chemist Alfred Carter testified that its bitterness would be hard to miss, leading to theories it was masked in a strong drink like the porter Frances sipped that night, though no guest reported odd flavors. Alternatively, experts considered a pill or medicinal tonic—common in small doses then—since Frances wouldn’t taste it that way, yet no such evidence surfaced. Injection was dismissed, as her body bore no marks. The missing strychnine bottle, later found in the garden, deepened suspicions of foul play, hinting someone disposed of it or planted it to suggest suicide. Joseph Marks’s mention of a bitter glass only fueled debate: had Frances ingested it unknowingly, or had someone slipped it to her, undetected until her final, agonized cry?

The coroner was now suspicious that the death was caused by wilful murder. Though what was the motive? After hearing statements from witnesses alluding to an affair between Joseph Marks and Frances Payne, he began to suspect she could have been pregnant when she died. The coroner ordered the exhumation of Frances Ann Payne’s body to conduct a second post-mortem, and the inquest was adjourned.

Medical Examination and Exhumation – September 18, 1884

The body of Frances Payne was exhumed to conduct a second post-mortem examination to address lingering questions. Doctors Knaggs, Collins, and Nott conducted an examination of the decaying cadaver, focusing on the uterus to check for signs of pregnancy or any motive linked to inducing an abortion. They found no evidence of recent pregnancy or other abnormalities, and she was reinterred for the final time.

Final Inquest – Late September 1884

The final inquest sessions included more testimonies from those close to Frances Payne, including her servants, Mr. Long, and friends. The coroner’s summing-up highlighted three possible explanations for her death: suicide, accidental ingestion, or murder.

The coronial inquest into Frances Ann Payne’s mysterious death by strychnine poisoning concluded with a verdict of willful murder by a person or persons unknown. The jury ruled that Frances had not died by suicide or accidental poisoning but had instead been deliberately poisoned. However, despite strong suspicions surrounding key individuals—particularly Joseph Marks and Charles Long—there was insufficient evidence to formally charge anyone with the crime.

The verdict left the case officially unsolved, as the coroner and jury could not determine who had administered the poison. The inquest exposed numerous inconsistencies and suspicious circumstances, including Frances’s close financial dealings, the mystery surrounding the missing strychnine, and the late discovery of a poison bottle in her garden. However, without a clear murder weapon, a witness to the poisoning, or definitive forensic proof, no one was ever held legally accountable for her death. It remains a cold case.

As the weeks turned into months, interest in the case began to fade. The Payne family distanced themselves from the scandal, and the social set in Melbourne pretended as though Frances had never existed. The socialites of Sydney society moved on to the latest affair to gossip about, and Frances’s only son, William Thomas Payne, inherited her estate, selling Como House and pursuing a venture in sheep grazing in the regional outskirts of Sydney.

Overlooked suspects?

Reports on the murder of Frances Ann Payne largely ignored suspects who, in retrospect, stood to gain the most from her death—the Payne family. Let’s start with William Thomas Payne, Frances’s only child, who stood to inherit her entire estate upon her death. Despite being her sole heir and a key beneficiary, William T. Payne does not appear to have been called as a witness or to have provided any formal testimony regarding his mother’s household affairs, finances, or relationships. His absence from the inquiry is notable, considering the financial implications—his mother’s vast wealth would now pass directly to him under the terms of his late father’s will.

Although he was only 19 at the time, it is conceivable that someone could have influenced him or acted on his behalf to expedite his inheritance. Soon after his mother’s death, William T. Payne embarked on an ambitious plan to construct a grand mansion on a rural estate in Narellan, an effort to emulate his wealthy uncle, Thomas Budds Payne, and impress his young bride. The mansion, completed in 1889, was named Studley Park. With Frances out of the picture, William had the financial means to pursue these ambitions without constraint.

Then there was Thomas Budds Payne, the 22nd richest man ever to have lived in Australia. Adjusted for inflation, his wealth in 2024 would be an estimated $6 billion. Residing in the grand palatial mansion Maritimo in South Yarra, Thomas was an immensely powerful figure. Though widely regarded as generous and charitable, even the most magnanimous men have their limits. He and his brothers, William and John, were among Melbourne’s earliest settlers and had painstakingly built their wealth from nothing, helping transform the city into one of the richest in the world. To see a woman—24 years his junior—inherit his late brother’s fortune, flaunt her newfound wealth, and disregard traditional mourning customs by engaging in an affair with an opportunistic lawyer must have been a deep insult to his sense of family pride.

Could he have arranged for Frances to be poisoned, ensuring that the estate passed to his nephew and remained within the family? While the theory is intriguing, no evidence ever surfaced to substantiate it. Nonetheless, Frances’s death conveniently restored the Payne fortune to its original lineage, raising lingering questions about whether the widow’s fate was truly an unfortunate accident—or an orchestrated end.

The Aftermath: A House Renamed, A Story Forgotten

In the wake of the scandal, Como House could no longer escape its association with the mysterious death. The Italianate mansion became a place whispered about with a mixture of fascination and dread. In an attempt to shed the taint of tragedy, the house was renamed Havilah, marking a fresh chapter for the property. The mansion at 61 Ocean Street, Woollahra, remained a silent witness to the events of that fateful night. It was built in 1883, a mere year before Frances’s death, and had seen the last chapter of her life unfold within its walls. Though its name had changed, those who knew the story still referred to it as the house where the spirited heiress met her untimely end.

The mystery of Frances Ann Payne’s death, with its layers of wealth, secrets, and possible betrayal, endured as one of Sydney’s most tantalising unsolved cases, although completely forgotten until now. It was a story with all the elements of an Agatha Christie novel: a wealthy widow, a circle of intriguing suspects, and a murder that had confounded the best detectives of the day. The answers, if they existed, were buried with Frances, leaving behind an enigma that would echo through the halls of Havilah for generations to come.

Today, Havilah is the home and office of Amanda Love of LoveArt, an international art advisor with an office in New York.