On the morning of 5 November 1850, inside the high sandstone walls of Darlinghurst Gaol, a young Aboriginal man known as Mogo, also recorded as Mogo Gar, walked calmly toward the gallows. His lips moved gently in prayer as Reverend Bodenham and Reverend Wilkinson supported him on either side. He stepped forward firmly, with a composure that stunned the small group as they walked through the gates towards the scaffolding surrounded by a crowd of hundreds. Moments later, Mogo stood on the scaffold as the executioner drew the bolt. The trap fell. Mogo died instantly. Tragically, his companion in death, James Whelan, did not.

The newspapers would later reveal that the hangman had mistakenly swapped the ropes intended for each man. The longer rope—meant for Whelan—was placed around Mogo’s neck, giving him a fall long enough to break his neck instantly. Whelan received the shorter rope, causing him to strangle slowly over several agonising minutes. The grim irony of this mistake underscored a larger truth: Mogo should never have been on that scaffold at all. For although he was convicted of the murder of a settler named Daniel Page, everyone involved in the case—including Page himself—agreed that Mogo did not strike the fatal blow.

This is the story of how a Djangadi (Dainggatti) man from the Macleay River region came to be executed for a killing that another man committed; how colonial law transformed a chaotic frontier encounter into a capital crime; and how Mogo, a man raised between two cultures, was abandoned by both in the moment he most needed justice.

The Frontier World of the Bellinger River

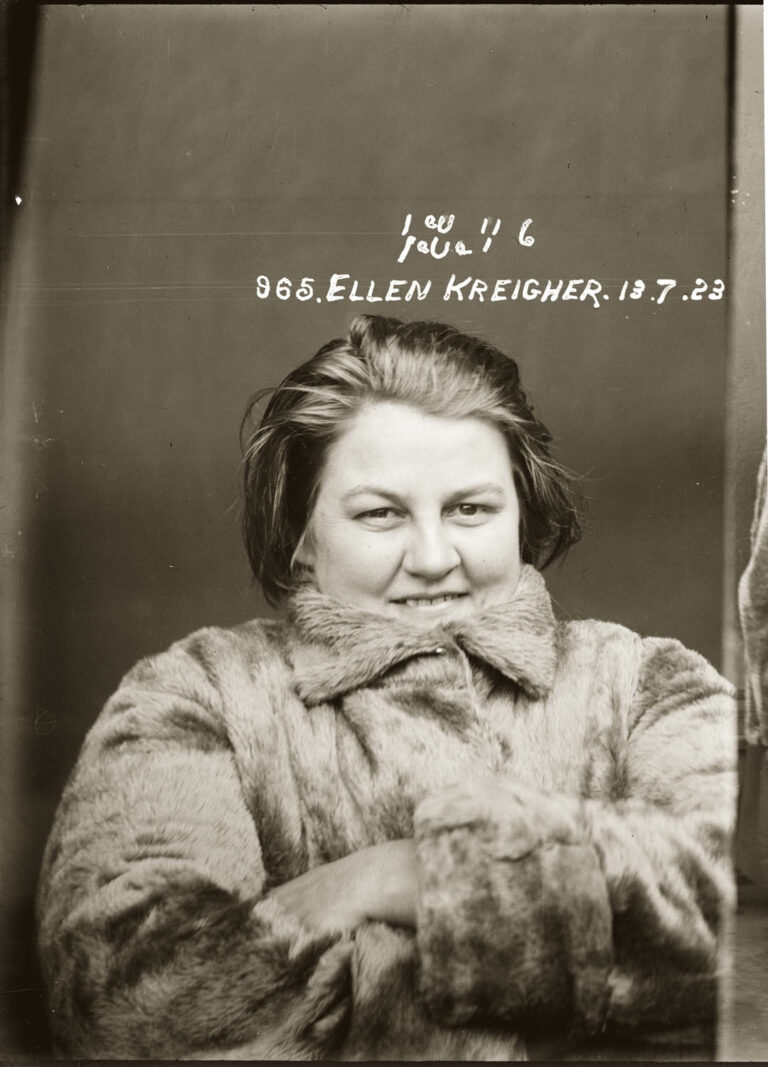

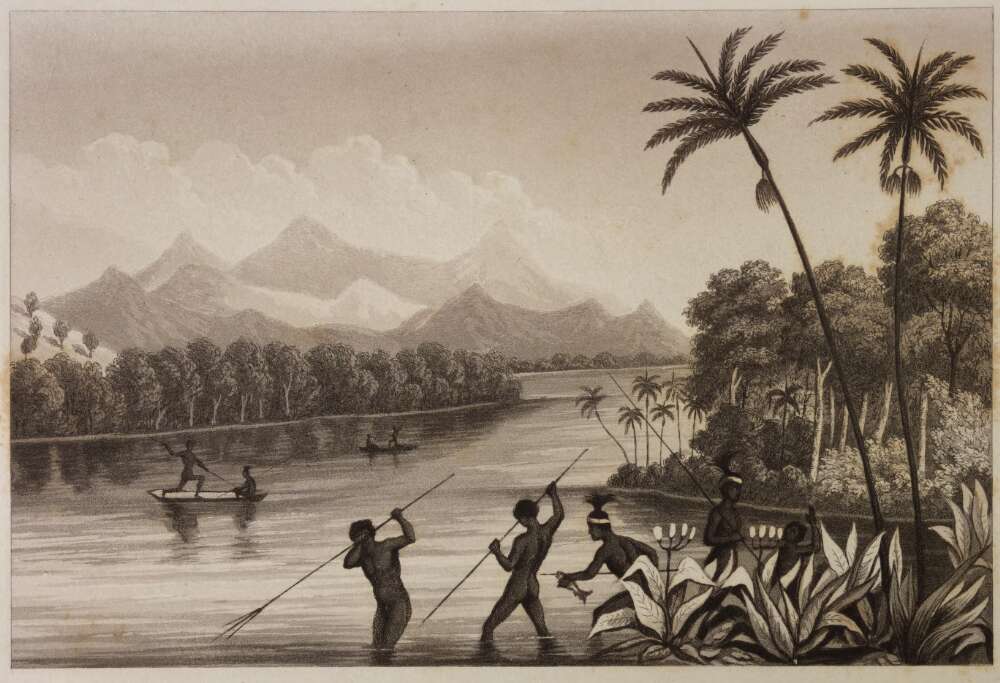

By the late 1840s, Gumbaynggirr Country along the Bindaray Yurruun or Bellinger River was undergoing rapid transformation. Cedar cutters, sawyers, and timber dealers had moved into the region, pushing deep into the forests. The river became a hub of extraction and conflict, its banks crowded with makeshift huts, stockpiles of timber, and rough frontier outposts.

One such settler was Daniel Page, a timber dealer who lived with Mary O’Neil and her young child. A man named Hayley was staying with them in April 1850, helping with the logging operations. Into this world walked Mogo. For some time, he had been visiting the hut, performing small tasks and interacting with the settlers—far more peacefully, it seemed, than many other cross-cultural encounters of the era. His visits were routine, and nothing in the record suggests previous hostility.

25 April 1850: A Morning That Turned Deadly

On the morning of 25 April 1850, Mogo entered the hut and offered to take rations to the nearby sawyers. Page agreed and left the hut with him to ferry him across the river. Once outside, however, four other Aboriginal men appeared, known locally as “Doughboy,” “Mickey,” “Charlie,” and Ugly.” [Clearly, these were not the men’s real names; however, as their true names do not appear in the archival records, they will be referred to by the above terms, with the acknowledgement that these labels were derogatory.]

What happened next unfolded quickly.

One man hurled a spear at Hayley. Hayley fled back to the hut. Page followed, but not before being beaten as he tried to retreat. The group of men then launched a chaotic attack on the hut, throwing boomerangs and firesticks and even prying a slab from the chimney to gain entry. Page and Hayley eventually made a desperate sortie from the hut with knives, briefly scattering their attackers. But the respite was brief.

The attacking group refocused their efforts on the storeroom, separated from the main hut by a low internal partition. Page crossed into this space to defend it. A brief scuffle was heard. When he returned moments later, he was clutching his neck. He had suffered a new wound, one he immediately declared to be mortal.

And then he spoke the words that should have exonerated Mogo: “Ugly did it.”

Every witness agreed.

A Dying Man in the Mangroves

After the attackers were finally persuaded to leave—only after being given the rations they demanded—Hayley, O’Neil, and several sailors from a cutter made two attempts to move Page to safety. Twice they tried to carry him to the vessel, and twice they failed. Weak from blood loss and wracked with pain, Page begged to be left on the opposite bank, concealed among the mangroves, with only a pair of blankets and a pillow for comfort. He survived the night. By the following morning, when help arrived again, he was still unable to walk and had to be left a second time. When the rescuers returned later, they found Page lying exposed on a beach, his blankets gone. Page told them that Mogo and his companions had returned, taken the blankets despite his pleas for mercy, and that Mogo had told him he “would not be cold that night, but dead.”

Page was eventually taken back to his hut, but the wound to his neck proved fatal, and he died on 28 April. Investigating police documented that three bags of flour, along with sugar, tea, tobacco, pipes, cooking utensils, bedding, and a small boat moored at the wharf, had been taken during the raid. Medical assistance from the Macleay did not arrive until two days after Page’s burial. His body was exhumed and examined by Dr Benjamin, who found the oesophagus completely severed and extensive bruising to the abdomen and head from blows inflicted by stones. In his opinion, the injury to the throat alone was sufficient to cause death.

Rumours soon spread that some of the Aboriginal men involved in the attack were the same individuals suspected of murdering two men, a woman, and a child on the river in April 1846. By mid-May, five policemen had been dispatched to pursue the fugitives across the rugged country.

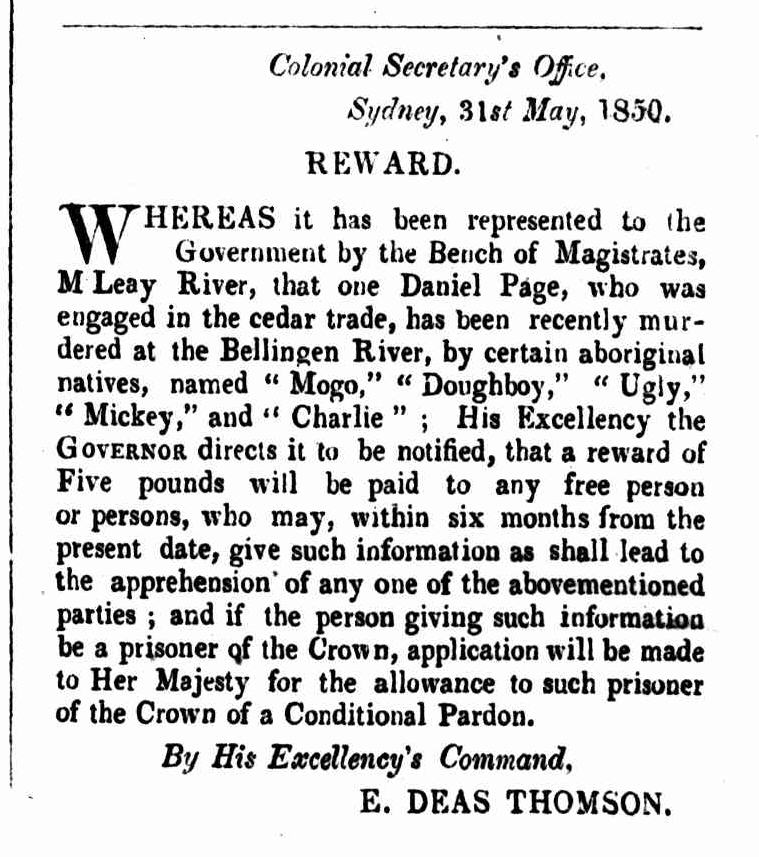

The Arrest and the Incomplete Justice

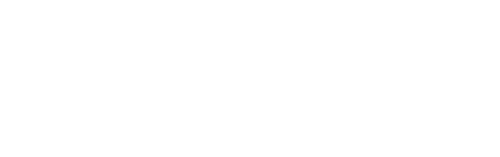

A manhunt commenced across the region with a five-pound reward offered by the Crown for the capture of one or all of the fugitives. Mogo was arrested later near the Macleay River, his home region. He was wearing a shawl belonging to O’Neil, taken from the hut after its occupants fled in panic.

This circumstantial detail would later be used to paint him as a looter and therefore implicitly guilty.

Meanwhile, Ugly, the man repeatedly identified as the killer, was never pursued. Newspapers admitted that local whites knew who he was, but there were “not sufficient numbers” available to attempt his capture. After this admission, all official efforts ceased, although a warrant and the reward stood.

Mogo, the only Aboriginal man taken into custody, became the sole carrier of collective blame for a group attack rooted in complex frontier tensions.

The Trial: A Sentence Rendered Before It Began

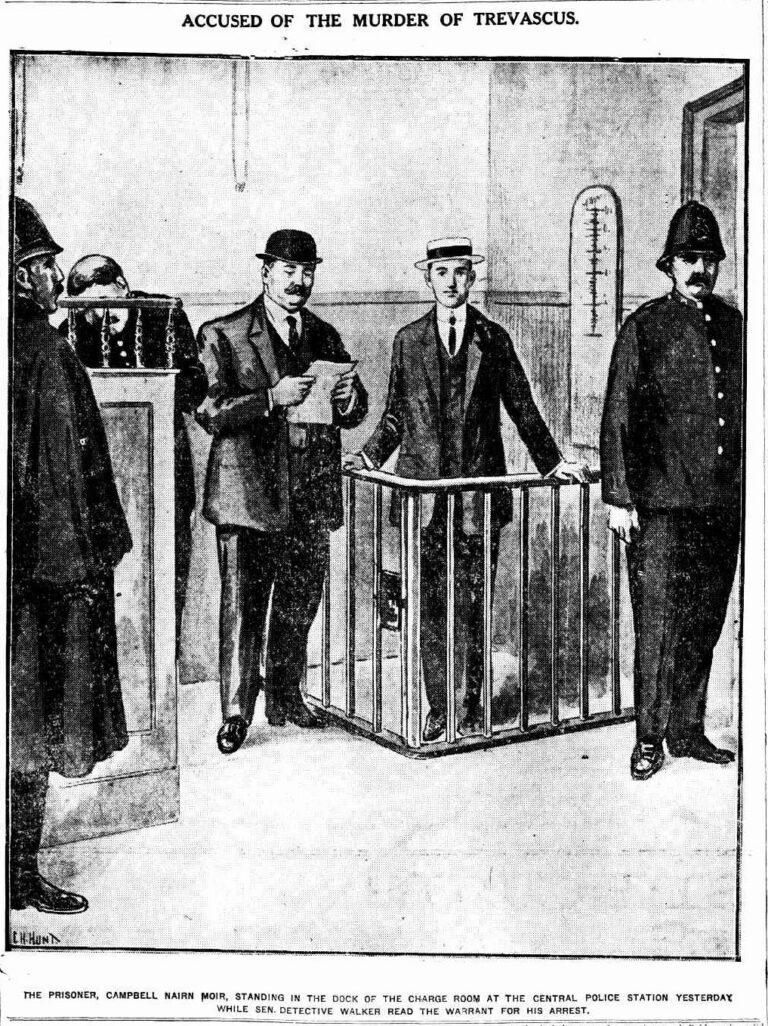

When Mogo Gar was brought before the Central Criminal Court in Sydney on 7 October 1850, the outcome of his trial was, in many ways, already sealed. The courtroom, presided over by Justice Dickinson, was a formal arm of the British legal system, yet it operated under the shadow of frontier tensions, racial prejudice, and settler fear. These forces shaped the proceedings as surely as any statute or precedent.

From the outset, Mogo was placed at a profound disadvantage. He had no lawyer of his choosing. Instead, the court asked barrister, Mr Holroyd, merely to “watch the case” on his behalf—a courtesy rooted more in procedural optics than in genuine representation. Holroyd was not instructed to mount a defence, call witnesses, challenge the admissibility of evidence, or present alternative narratives. His role was passive and supervisory, leaving Mogo effectively voiceless in a system already predisposed against him.

Meanwhile, the Crown was represented by the Solicitor-General, a clear signal of the prosecution’s seriousness. Yet the prosecution did not attempt to prove that Mogo struck the fatal blow. They openly acknowledged that Daniel Page, while dying, named another man—known as “Ugly”—as the attacker who delivered the wound to his neck. No witness ever claimed otherwise. No evidence placed a weapon in Mogo’s hands. No testimony described him as violent in the critical moments of the attack.

But the Crown did not need to prove individual guilt.

Instead, they relied on the legal doctrine of common purpose, a provision that transformed a chaotic frontier confrontation into a capital crime. Under this doctrine, if several individuals acted together in a robbery or violent enterprise, any murder committed in the course of that enterprise was legally attributed to all participants, regardless of who struck the blow.

This legal concept, transplanted from English common law into the vastly different social and cultural landscape of New South Wales, proved devastating for Aboriginal defendants. It erased individuality, nuance, and circumstance. A person’s mere presence among a group was enough to implicate them fully, especially when that person was Indigenous, and the victims were settlers.

Holroyd attempted a limited defence, arguing that there was “not the slightest proof” that Mogo inflicted the fatal injury. But without the authority or instruction to mount a full argument, his intervention was little more than symbolic. He did not challenge the prosecution’s assumptions about shared intent. He did not question the reliability of panicked settler testimony. He did not raise the cultural complexities of Aboriginal group dynamics, kinship obligations, or the possible motivations underlying the conflict. Nor did he point out what seems obvious today: that the real killer, Ugly, was never pursued by authorities, despite being well known in the district.

Justice Dickinson’s summing-up to the jury removed any remaining ambiguity. He acknowledged the evidence that Ugly delivered the fatal wound—but reminded the jury that if they believed Mogo was “associated with the others” for the purpose of robbery or violence, then in the eyes of the law, the act of one was the act of all. It was a simple, devastating instruction, one that reframed the case from a question of guilt to a question of presence.

Justice Dickinson told the jury:

If the prisoner had been associated with the others for the purpose of committing a robbery… the act of any one of them, in the prosecution of their design, would be regarded in law as the act of the whole.

The trial lasted only hours.

The jury deliberated for only forty-five minutes before returning with a verdict of guilty of wilful murder.

Dickinson wasted no time in pronouncing the sentence: death by hanging, with “no reasonable hope of mercy” extended. He declared that the punishment was needed:

“…not for purposes of vengeance… but for the sake of deterring others…preventing the spread of crime in the interior.”

In that courtroom, under the weight of racialised legal doctrine and colonial fear, Mogo never truly had a chance. The verdict had less to do with what happened on the Bellinger River and more to do with what the colony needed the trial to represent: control, retribution, and the reaffirmation of settler authority.

Thus, the life of one young Djangadi man was made a message to all other Aboriginal people living along the frontier.

Calls for Mercy: A Cry Unheard

In the days following Mogo’s conviction, a small but powerful chorus of voices emerged from the colonial press calling for mercy. Though colonial newspapers were often hostile toward Aboriginal people, the injustice of Mogo’s sentence was so stark, so deeply disproportionate, that even some of the loudest champions of frontier discipline could not ignore it.

The most forceful plea appeared in Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, a newspaper not known for excessive sentimentality. Its editorial of 12 October 1850 cut through the legal formality of the trial and spoke directly to the moral heart of the matter:

It was distinctly proved upon the trial that Mogo’s was not the hand which sped the fatal boomerang.

This single sentence exposed a truth the court had twisted into irrelevance. The editor continued, emphasising that another man—Ugly—had been identified repeatedly as the killer, and that Mogo had been condemned not for what he did, but for who he was and who he happened to be with. In passionate prose rarely seen in colonial reporting on Aboriginal defendants, the paper implored the colonial Executive—the Governor and his advisers—to intervene:

But if under circumstances it be occasionally deemed expedient to depart from the strict letter of the statute, surely this is a case for the exercise of that high prerogative which, “becomes the throned Mo-narch better than his crown.”

It was an appeal to the most sacred political mechanism available in the British legal tradition: the power of clemency. The editor argued that the law’s rigidity should not eclipse justice, that the purpose of mercy was precisely to correct such miscarriages when the law, through its formal logic, delivered a verdict out of step with fairness or humanity.

What made this call even more striking was that it did not attempt to excuse the attack on the settlers. Nor did it romanticise Aboriginal resistance or downplay the fear experienced by Page and Hayley. Instead, it focused squarely on individual responsibility—on the idea that while the law recognised collective guilt, the moral world did not.

Another newspaper described Mogo as “a wretched victim of circumstances,” a man swept into a violent situation he did not control. These voices understood, perhaps better than the court, that Mogo had lived much of his life in the gap between cultures. Raised by settlers, yet still Aboriginal in the eyes of the law and the colony, he belonged fully to neither world—and thus had no one to protect him when the weight of the state bore down.

Yet despite these pleas, no mercy came. Governor FitzRoy and the Executive Council were well aware of the frontier anxieties gripping the districts north of Sydney. Relations between Aboriginal groups and timber-getting settlers were tense. The government feared retaliatory attacks. In such a climate, hanging Mogo served a political purpose: it reassured settlers that the state would respond to Aboriginal resistance with uncompromising severity.

To grant clemency would have required extraordinary courage—a willingness to elevate justice over frontier politics. Newspapers like Bell’s Life recognised this, warning that executing a man for a crime he did not personally commit would do nothing to stabilise the frontier and everything to stain the moral character of the colony. But theirs was a minority voice, drowned beneath the louder demands of those who sought swift, visible retribution. In the end, mercy was not merely denied; it was not even given meaningful consideration. No petitions circulated. No inquiries were made. No alternatives to execution were discussed. The machinery of colonial punishment moved forward unimpeded, carrying Mogo with it.

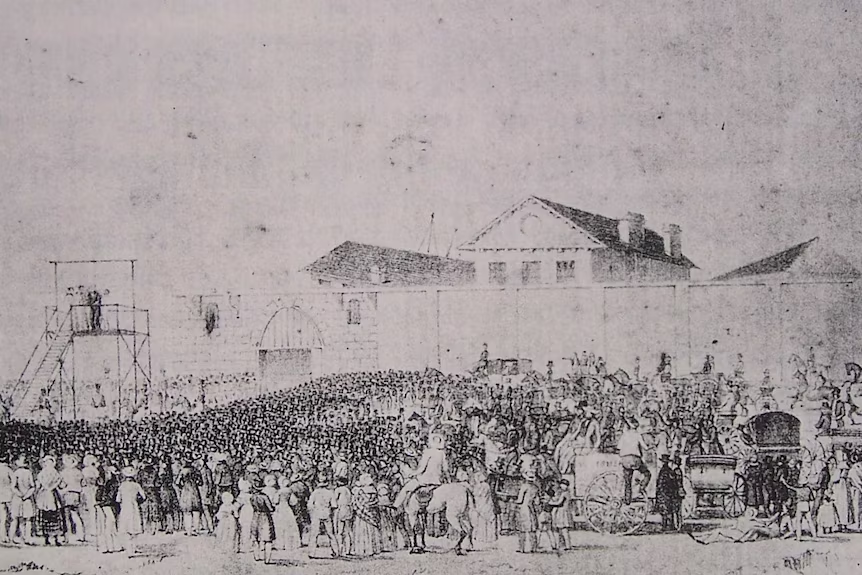

5 November 1850: The Day of Execution

The execution of Mogo and James Whelan on 5 November 1850 drew a vast crowd to the old Forbes Street gates of Darlinghurst Gaol long before dawn. Public hangings had become grim spectacles in colonial Sydney, attracting people from every walk of life. The newspaper, Bells Life in Sydney, described:

“A vast crowd had assembled there, composed of respectably dressed people — mechanics, laborers, vagrants, thieves, prostitutes, and (worst of all!!) mothers with infants in their arms and young ones by their sides.”

Many treated the event as entertainment rather than a moment of solemn justice. This carnival-like atmosphere, condemned by contemporary journalists, revealed more about the colony’s appetite for violence than any supposed moral lesson the law intended.

Inside the gaol, the mood was altogether different. Mogo, attended by Anglican clergy and visited the night before by the Archbishop of New Zealand, spent his final hours in prayer and remained notably composed. Though condemned for a murder he did not personally commit, he faced the gallows with quiet dignity. Whelan, supported by Catholic priests, expressed deep remorse for his crime. The two men—strangers in life, one Aboriginal, one European—were bound together in death by the machinery of colonial justice.

At nine o’clock, the death bell tolled, and the condemned were led to the scaffold. Observers remarked on Mogo’s steady walk and calm demeanour. After prayers were offered, a tragic error occurred: the executioner accidentally switched the ropes intended for each man. As a result, Mogo died instantly, his neck broken cleanly by a longer drop. Whelan, given the shorter rope, suffered a prolonged and agonising death by strangulation, struggling for several minutes in full view of the horrified crowd.

By ten o’clock, the bodies were cut down. Whelan’s remains were returned to his widow, while Mogo—far from his Djangadi homeland—was placed on a wagon and quietly taken away.

A Child Taken: The Origins of “Mogo”

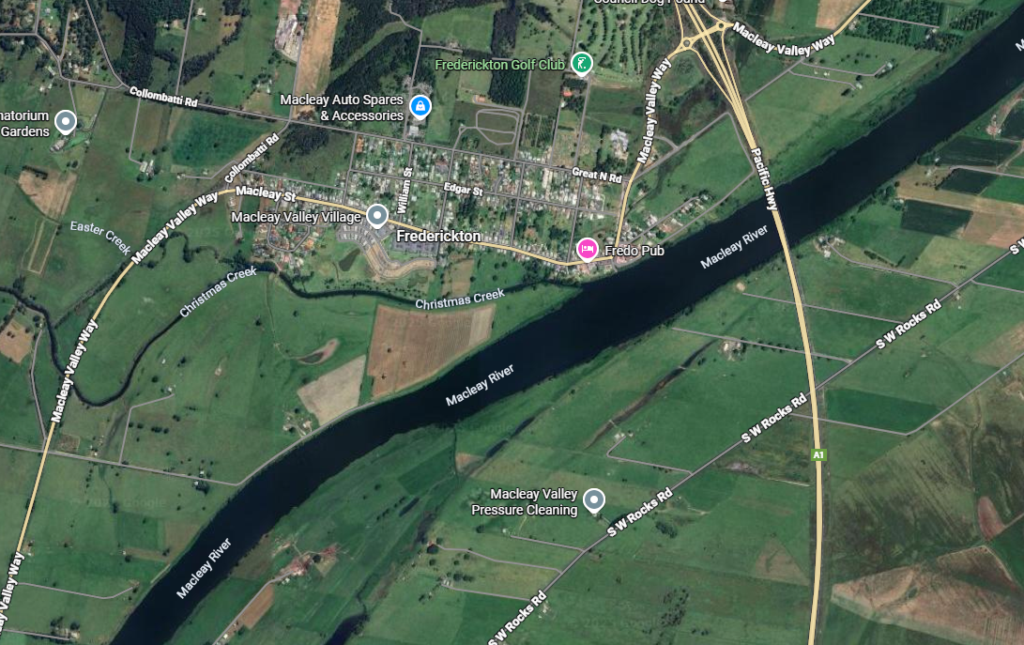

Mogo’s early years unfolded along the Macleay River, south of Gumbaynggirr country, on the lands of his Djangadi ancestors—a landscape of dense forests, tidal waterways, and deeply rooted kinship networks. By the time of his childhood, the Djangadi and neighbouring Aboriginal groups had already witnessed what had happened to their southern neighbours as colonial settlement advanced. They responded with determined guerrilla resistance: targeting shepherds, launching hit-and-run raids on outstations, and driving off sheep and cattle before retreating into the steep gorges where pursuit was nearly impossible. Frontier violence escalated sharply. In one of the most devastating reprisals—the Kunderang Brook massacre of 1840—between two and three dozen Aboriginal people were killed following accusations of sheep duffing. By the early 1850s, the conflict was nearing its brutal end. A detachment of Native Police was stationed at Nulla Nulla in 1851, cementing colonial control. But decades of killings, reprisals, introduced disease, and forced displacement had already taken a catastrophic toll. Of the roughly 4,000 Aboriginal people who had lived in the region before European occupation, historians estimate that up to one-third were killed within just twenty years—a devastating collapse of population, culture, and continuity. (see Harrison, 2004)

It was in this world of fear, upheaval, and resistance that Mogo was born. Like other Aboriginal children of the region, his early life would have been shaped by extended family, language, ceremony, and the seasonal rhythms of Djangadi Country. Yet his childhood was abruptly and irreversibly transformed by a dramatic encounter that newspapers would recount long after his death. A settler named Mr. Guard, lost in the bush, stumbled into a group of Aboriginal people who perceived him as a threat and prepared to attack. In a desperate attempt to save himself, Guard seized the nearest child—Mogo—and held him up as a shield against incoming spears and boomerangs. Shocked and fearing for the boy’s life, the adults halted their advance. Guard slowly retreated toward the river, the child still in his arms, until a boat came into view. As he stepped aboard, the group called out to the boy, crying “Mogo!”—meaning “come back.” But Guard rowed away, taking the child with him.

At Guard’s station, Mogo was fed, clothed, and raised within settler society. For the next decade, he lived between cultures—no longer part of his Djangadi community, yet never accepted as an equal by the colonial world that claimed to protect him. He learned English, received basic schooling, and was brought up as an Anglican; by adulthood, he could read and write. Guard’s surname, softened by local usage, became attached to him, transforming “Mogo Guard” into “Mogo Gar.” What Mogo’s true name was, we will never know.

Despite these outward signs of Europeanisation, Mogo remained marked by the profound dislocation of being taken from his people: the loss of family, language, and cultural world. However much colonial society attempted to mould him, his Aboriginal identity continued to determine how he would be seen and treated—most tragically in the courtroom that would later condemn him for a crime he did not personally commit.

Laid to Rest on Foreign Country

Mogo’s body was carried to the burial ground of St Stephen’s Church, Newtown, where he was laid to rest on 5 November 1850. Because he had been condemned for murder—and because he was an Aboriginal man—he was interred on the far edges of the cemetery, well away from the church building itself. There he remained for more than one hundred and seventy years: a Djangadi man buried on other people’s Country, over four hundred kilometres from his ancestral homeland on the Macleay River.

Today, a tree and a small sandstone marker stand above his grave along Lennox Street, Newtown. The plaque reads:

“THIS TREE WAS PLANTED TO THE MEMORY OF MOGO, AN ABORIGINAL WHO WAS BURIED HERE ON 5TH NOVEMBER 1850.”

It is a quiet memorial—easily missed, yet deeply poignant. A reminder of a life lived between two worlds, shaped by forces far beyond his choosing. Next time you walk along Lennox Street, just before reaching Eliza Street, pause at Mogo’s resting place. Reflect on the young man whose story speaks to the greater tensions of his time: between settlers and Aboriginal people, between colonial law and human survival, and between cultural worlds that would never fully understand one another.

The Capture and Trial of Doughboy, 1859-60.

For nearly nine years after the killing of Daniel Page at the Bellinger River in 1850, the man known as Doughboy remained at large, an ever-present rumour on the Macleay and Bellinger, yet always vanishing before the police could lay hands on him. His reputation for strength and ferocity deterred settlers from attempting his capture, and even the Native Police had failed to corner him. That changed on the night of 6–7 August 1859, when Lieutenant Poulden of the Native Mounted Police received intelligence that Doughboy was camped near Christmas Creek on the Macleay. Moving on foot with four troopers and guided by “Clarence River Jimmy,” they crossed the river under cover of darkness and crept through reeds toward a cluster of five or six gunyahs. Within one of the bark huts, faintly lit, sat Doughboy. At the word, the troopers rushed the camp. Doughboy leapt for a loaded firearm at his side and pulled the trigger point-blank at Poulden—only the absence of a percussion cap prevented the lieutenant’s death. What followed was a savage melee in the dark, with tomahawks and nulla-nullas flying. Trooper Carlo seized Doughboy by the hair, refusing to let go despite bites and blows, and after half an hour’s struggle, the fugitive was finally subdued and handcuffed.

The camp quickly scattered once it became clear Doughboy was the sole target of the police, but crossing the river with him in custody proved almost as perilous as the arrest. He fought with such violence that the troopers struggled merely to keep him in the boat. By dawn, he was marched into West Kempsey and placed in the lock-up to await examination. The arrest caused a sensation throughout the district—here, at last, was one of the surviving men accused of the attack that had killed Daniel Page and terrorised settlers along the Bellinger nine years earlier. Newspapers pointedly reminded readers that Doughboy had evaded justice while his co-accused, Mogo, had been captured in 1850, sent to Sydney, and hanged. Others, including the notorious “Ugly” and “Blue Shirt,” continued to elude police. A first attempt by Lieutenant Poulden days earlier to capture Ugly had ended in disaster when a large group of Aboriginal men resisted, knocking a ticket-of-leave assistant senseless with a nulla-nulla and forcing the officer to retreat.

When Doughboy was finally brought before the Central Criminal Court in December 1859, many of the ambiguities that had clouded Mogo’s trial reappeared. Witnesses struggled to clearly identify who had struck the fatal wound. Jane O’Neil, Page’s partner of nine years, testified that she saw Page’s throat cut when he opened the store-room door, but she could not say who inflicted the blow. She confirmed Doughboy’s presence and that he helped carry away provisions, but she did not witness him committing violence. Haley, Page’s mate, likewise could not firmly state that Doughboy inflicted the wound. Crucially, Page himself had lived nearly forty-eight hours after the attack—long enough, the defence argued, for a second wound to have been inflicted by those who later returned to steal his blankets. The medical testimony was equally ambiguous. Dr. Macfarlane explained that a man could survive two to three days even if the windpipe were severed, but noted that improper treatment, exposure, or a secondary injury could hasten death. The defence emphasised the legal and moral difficulty of convicting an Aboriginal man when Aboriginal witnesses were, by law, excluded from giving evidence on oath. The Attorney-General, however, argued that Page’s death was the direct and foreseeable outcome of the unlawful attack in which Doughboy had participated.

The jury deliberated only briefly before returning a verdict of guilty, and Doughboy was sentenced to death—left in the condemned cell at Darlinghurst to await the Executive’s decision. Public reaction was divided. Bell’s Life reviewed the testimony and declared it “far from conclusive,” calling for mercy on the grounds of both Doughboy’s uncertain participation and the structural disadvantage placed upon Aboriginal defendants. In early 1860, the Executive Council yielded to these appeals. Doughboy’s death sentence was commuted to fifteen years’ labour on the roads, a punishment still severe but a stark contrast to the fate of Mogo nine years earlier. His commutation, widely reported in the colonial press, demonstrated the shifting winds of judicial sentiment—an acknowledgment, however limited, that frontier justice had often been handed down in haste, and that the legal system’s treatment of Aboriginal men required, at times, a tempered hand.

By Elliot Lindsay, December 2025

References List

“THE MURDERS BY THE BLACKS AT BELLINGER”

The Star (Sydney, NSW) 1846, ‘Metropolitan’, The Star, 10 April, p. 1, viewed 11 December 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228065008

“MURDER OF A WHITE MAN BY THE BLACKS.”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 11 May). Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842–1954), p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE MURDER OF DANIEL PAGE”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 13 May). Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842–1954), p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE BELLINGER MURDER.”

The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (1850, 15 May). p. 2. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE BELLINGER MURDER – INQUEST”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 20 May). Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842–1954), p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE BLACKS OF THE BELLINGER”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 27 May). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE BELLINGER MURDER”

The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (1850, 29 May). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE BELLINGER MURDER”

The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (1850, 12 June). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE ABORIGINAL MURDERER MOGO”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 14 June). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE ABORIGINAL MURDERER, MOGO”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 20 June). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“EXECUTION OF MOGO”

Sydney Morning Herald (1850, 9 November). p. 5. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE EXECUTION OF MOGO”

Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer (1850, 9 November). p. 2. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“MACLEAY RIVER. CAPTURE OF THE ABORIGINAL MURDERER ‘DOUGHBOY'”

Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (1859, 18 August). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“KEMPSEY, MACLEAY RIVER”

Empire (1859, 18 August). p. 2. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“The New Moon”

Sydney Morning Herald (1859, 5 September). p. 3. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT – MURDER.”

Empire (1859, 7 December). p. 2. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“THE CONDEMNED ABORIGINAL”

Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer (1859, 24 December). p. 2. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/

“SYDNEY.”

Pastoral Times and Deniliquin Telegraph (1860, 27 January). p. 2. Retrieved from https://nla.gov.au/