The Battle of Market Street – 1900

By ELLIOT LINDSAY

The doors to the old Victoria Barracks on Oxford Street violently swung open, letting in the chilled air of a late Autumn night. In charged a soldier of the permanent artillery, dishevelled in appearance, his clothing stained with blood.

“Those bastards from Engine Street attacked Johnson! He is in the hospital and in a terrible state.”

It was a Saturday night; the artillerymen had been celebrating a decisive victory for the Empire in its war against the Boer in South Africa. Most men had already returned to the barracks, sleepy from the schooners of ale swilled down in the city’s many hotels. Nonetheless, the soldier’s call aroused the men from their quarters.

“You’re bloody joking! I saw those scoundrels scurrying around the streets,” replied one comrade.

“And on this night of celebration,” responded another.

“Come on! Let’s go get the bastards, once and for all.”

Brought to anger by the news of their injured comrade, the artillerymen threw on their boots and tunics. They armed themselves with clubs and stormed out of the barracks and towards the city.

In the late nineteenth century, the people of Sydney were terrorised by the urban street gangs that dwelt in the gritty alleys and laneways that crisscrossed the old industrial inner suburbs. In those days, the gangs were known as ‘pushes’ and every street corner had one. A push was made up of ‘larrikins’, young males from blue-collar communities that congregated in large groups smoking, drinking, spitting and yelling abuse at pedestrians. By 1900, the people were in a state of hysteria after several pushes had committed a series of blood-curdling atrocities that included rape and murder.

The most notorious push of the time was found in Haymarket, called the Engine Street Push. If you are wondering where Engine street is today, you would have to look under the concrete floor of Paddy’s Markets. However, a tiny bit of Engine Street still exists: it is now the part of Ultimo Road between George Street and Thomas Street that leads to the entrance of the market building. It was to Engine Street that the enraged artillerymen of the Victoria Barracks came to seek their revenge against the Engine Street Push.

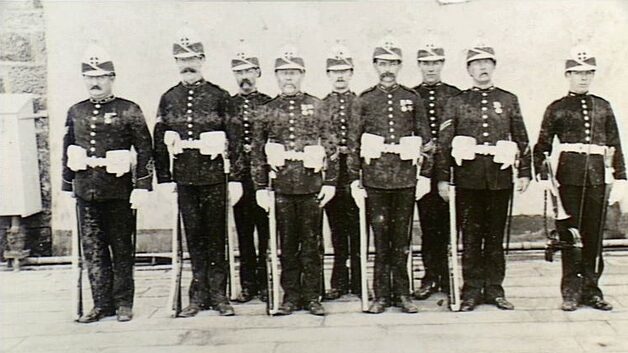

Typically, the pushes of Sydney spent most of their time battling against each other for control of various neighbourhoods. The Engine Street Push would clash with the Bathurst Street Boys, the Abercrombie Boys of Chippendale or the Gipps Street Push of Surry Hills. However, the thing they enjoyed most was beating up the cops. Yet, since the NSW Police Force had been armed with pistols in the late 1890s, fewer larrikins were willing to tangle with the cops. Nevertheless, they quickly discovered that sailors and military men were just as ready to brawl. Rumbles with drunk artillerymen from Victoria Barracks were commonplace and typically had no repercussions for the young larrikins. Although they didn’t know it yet, they had gone too far this time.

When the riled-up artillerymen arrived at Haymarket, the push was nowhere to be seen. But the soldiers were not surprised; they knew the push would hide in the slums until the opportunity to attack their outnumbered victims arose. Revenge was not to be had this evening, but the soldiers weren’t willing to let it go as they had done before. Just like Lord Roberts planned his attacks against the Boer guerillas in South Africa, they too would plan their attack against the Engine Street Push.

Back at the barracks, the soldiers strategised their attack. They knew the push would not face them if they believed they were outnumbered. So, the soldiers would need to break up into groups. Furthermore, the ‘captain’ of the push and his cronies could be found anywhere between Belmore Park and Market Street. This meant the small groups of soldiers would have to act as scouting parties with runners to coordinate and communicate. If one group found the push, runners would notify other groups of their location. The push would then be surrounded in a pincer movement and beaten mercilessly.

The following Thursday, reports came back that the enemy was loitering around Market Street between George Street and Pitt Street. The excited artillerymen advanced to the location where they successfully located their target. Armed with lead pipes and heavy iron belt buckles, they surprised the Engine Street Push at Market Street and Pitt Street, where the fashion retailer Zara stands today.

Sixty artillerymen surrounded and attacked the push with a ferocity unseen on the streets of Sydney before. At first, the push was only a few dozen and significantly outnumbered, taking a severe beating. However, more larrikins began to arrive and join the ranks of their push comrades. Pretty soon, the push numbers were in the hundreds. The battle waged up and down the streets. The police tried to break it up; however, there were not enough of them to have any influence. The word spread and approximately one thousand pedestrian onlookers appeared to spectate. Many of them were cheering on the artillerymen.

After several hours of hard fighting, the wounded began to tally up. Soldiers, pushites and even several non-combatants were found battered and bruised with split heads on the ground. Market Street and what is today Pitt Street Mall was covered in blood. A battalion of NSW Police officers then arrived at the scene and joined the melee. They eventually took control of the situation and rounded up the ringleaders from both sides of the battle.

The Battle of Market Street was a significant shock to the people of Sydney. The press provided extensive coverage of it and the events that followed. The press reported that thousands of larrikins descended upon the city the following Saturday, anticipating another clash. They behaved poorly and beat up several people, including a six-year-old boy and an elderly man. Then, in July, several members of the Engine Street Push and NSW Permanent Artillery were charged with assault and committed to stand trial.

By this point, the authorities were well aware that they needed to crack down on larrikinism, pushism and the anti-social behaviour found on the streets of Sydney. But it wasn’t the police that brought an end to the push. In 1900, the bubonic plague broke out across the slums of Sydney, and the city council decided the slums needed to be cleared. Engine Street was marked for demolition, and by 1909, it was buried under the new markets. Without the winding laneways and dark alleys to hide in, the old push gangs of the nineteenth century began to wither away. The streets of Sydney would not see similar gang violence until the Roaring Twenties and the rise of the razor gangs, but that is a story for another day.